September 17, 2012

Beginning September 7th, the Turkish Center for Islamic Studies (ISAM) and the Marmara University Institute for Middle East Studies hosted a noteworthy, two-day conference in Istanbul which gathered around 200 attendees, including two representatives from Hayya Bina. Held under the broad, conservative title “Arab Awakening and Peace in the Middle East: Muslim and Christian Perspectives,” the conference was clearly an attempt by Turkey to assert its growing political role in the region. To give the gathering a dramatic impact, the organizers described the event as nothing less than a groundbreaking interfaith dialogue initiative that involved leading religious figures from the Middle East and beyond.

Erdogan recounts history—to sway the present

Despite the seemingly naïve theme of the conference—which deftly sidestepped the question of sectarian complexities within Christian and Muslim communities—Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan made a rather bold and intriguing turn during his opening speech. Surprising his audience, Erdogan compared the ongoing crisis in Syria to the ancient Battle of Karbala: “What is happening in Syria is similar to what happened in Karbala, but the oppressed and the oppressors are different.” He added immediately, “I know very well that killing is religiously forbidden for Shiites [and]...Sunnis.”

President Erdogan’s mention of Karbala refers to the battle fought in 680 CE (year 61 of the

|

| Turkish Shiite women participate in a religious procession in Istanbul |

On one hand, Erdogan’s Karbala example underscored his desire to reach out to Shia audiences and sympathies. On the other hand, however, it highlighted the hypocrisy of the Assad regime and its supporters, all of who are betraying the most fundamental Shia values. In addition to the Turkish Prime Minister cautiousness not to denounce the Shia as a whole, his Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu promised in a later speech, “People being Sunnis, Alawites, Nusayri, Shiites or Christians does not matter for us. We defend the great old tradition of the Middle East, respect everyone who struggles for human dignity and I salute them.” As noted above, the event coordinators assembled representatives from diverse religious groups throughout the Middle East, and the religious validation received by such groups is a means through which Turkey can flex its new political muscle and demonstrate its understanding of the complex identities that are shaping the region’s transformation.

Erdogan, a Sunni, is no stranger to the importance of religious plurality, tolerance and the growing political influence of the Shia community. In fact,in 2010 he became the first Turkish Prime Minister ever to attend an Ashura ceremony. From the Zeynebiye neighborhood of Istanbul, the PM declared, “[the] martyrdom of Hussein was not a farewell but a reuniting...not an end but a start…. Karbala’s pain is still alive in our hearts, even after 1,370 years.” Those thoughts drew praise from Shia throughout the region, including controversial Iraqi cleric Moqtada al-Sadr.

Minority identity...or not

Despite these bold gestures, Turkey is still far from being able to gain the trust of Shia and Alavi minorities, a potential source of support which could guarantee success in Turkey’s drive to become the kingpin of Syrian revolutionary ambitions—and thus a regional leader. In part, this failure stems from Erdogan’s abnegation of the distinct differences that exist among his own country’s minority groups. For example, “less than half a million Alawites, speaking Arabic, live on the Turkish side of the border with Syria.” Alternatively, the Alevis, who are neither Sunni nor Shia, include “up to 20 million adherents in Turkey and among its Western European émigrés.” Within the halls of the Turkish government, however, with Erdogan at the helm, these two minorities are consciously grouped together. In the face of Alevi opposition to Turkey’s Sunni majority government, Erdogan chided last March: “Don’t forget that a person’s religion is the religion of his friend. Tell me who your friend is and I’ll tell you who you are.” Perhaps the Alevis’ notable lack of support for the revolution provides an additional pretext for the Turkish government’s policy to disenfranchise these groups politically, an eventuality that may cause a ripple effect in Turkey’s mission to achieve regional dominance through diverse partnerships. Ultimately, if Turkey desires to maintain its reputation as an egalitarian, regional leader, it must do more than utter politically inspired words about the Battle of Karbala. A daring political vision will necessarily come at the price of sacrificing entrenched prejudices which continue to thwart both domestic stability and external relations.

Reading the tea leaves

While several conclusions can be drawn from this conference, the preeminent notion is that it is impossible to engage in any form of Muslim-Christian “interfaith dialogue” without first examining the details that influence inter-Muslim hostility. Indeed, the religiopolitical fault lines that traverse the Middle East are far more complicated that the divisions that separate the Abrahamic religions. Not only do the paths blazed by this sectarian violence converge within and between the religions, they are also responsible for today’s interwoven conflict. As Turkey’s President of Religious Affairs (the country’s highest Islamic authority) Prof. Mehmet Görmez observed in a recent publication, “Today it is possible to see the role of religion behind many political borders, tensions and divisions in Turkey’s neighborhood. Shiism is extending its turf each day as a sect and the historical division of Islam risks being re-actualized.” Such analyses illustrate both Turkey’s acknowledgement of the pivotal nature of sectarian issues, as well as its apprehension of diversity within Islam.

Regarding the Christian presence in the Middle East, more often than not this group considers itself to have suffered from the collateral damage associated with larger conflicts and the changes wrought by these conflicts, particularly the predominant role played by Islamist forces. The crisis still unfolding in Syria simply underscores the dilemma that impacts Middle Eastern Christians: should they continue to support the dictatorial regime that guaranteed their security even while that government oppressed those who attempted to navigate the dangerous and unfamiliar path of change? Despite or possibly because of that dilemma, Christians have certainly been attacked solely because of their religious identity. Thus, the most challenging near-term problem for that demographic remains the “collateral damage” they may suffer because of fighting within the Alawite/Shia and Sunni camps, especially since the fallout from those conflicts will likely affect the Christian communities long before it does the belligerents. Christian attendees differed in their political outlook. Secretary of the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Religious Dialogue Miguel Angel Ayuso Guixot stressed that “the Syrian people are living in a tragedy and that is also their responsibility to end this violence in Syria. It is unacceptable for Christians to withdraw and stay silent instead of showing courage and making an effort for the establishment of peace.” Orthodox representatives asserted privately that “second-class citizenship was preferable to death,” thus echoing the dilemma noted above that continues to plague this community.

A “who’s who” among those who attended—and those who did not

The impact made by those who attended the conference was no more pronounced than that made by those who did not. Interestingly, Saudi Arabia—Islam’s literal and figurative Mecca—sent just three delegates to the conference. These were Sami Angawi, an expert on Islamic architecture and founder of the Amar Center for Architectural Heritage, his colleague Mohamad Anwar Ismail Deep, and a representative for Mr. Abdallah Ben Abdel Mohsen At-Turki, who serves as the General Secretary of the Muslim World League. Although these gentlemen are noteworthy intellectuals in their own right, none of them are high-ranking “officials” of the royal family or the religious courts. Understandably, this lack of official participation prompts the question: Why did Saudi Arabia neglect to send either a delegation or at least a bona fide, individual representative to such a significant regional conference?

Remarkably, not a single representative came from Qatar, a country whose excoriation of Syria’s Assad regime and support for the opposition movement exceeds even that of Turkey. Similar to Turkey, Qatar has been riding the coattails of the Syrian revolution in an effort to become one of the Middle East’s political VIPs. For instance, Qatar led attempts by the Arab political movement to oust Assad and has begun supplying weapons to Syrian rebels. By supporting the opposition, Qatar has become a target for retaliatory attacks such as recent Internet hackings of its Al-Jazeera TV network and Rasgas, the second-largest exporter of natural gas in the world.

Unsurprisingly, there were no Alawite attendees at the conference either; that situation only highlights the disparity between the event’s stated desire to engage in religious pluralism and the political reality of the day. Conference organizers informed Hayya Bina privately that invitations had been issued but were not accepted, and it was difficult to discern whether any of the Turkish participants represented the country’s sizable Alavi minority. The non-Sunni Muslim attendees, in this sense, were represented by Shia clerics and activists from Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon. Finally, although quite a bit was said at the symposium about the shared legacy of the Abrahamic religions, the conference hosts obviously did not want to embarrass attendees by inviting representatives from the Jewish community, either.

What comes next?

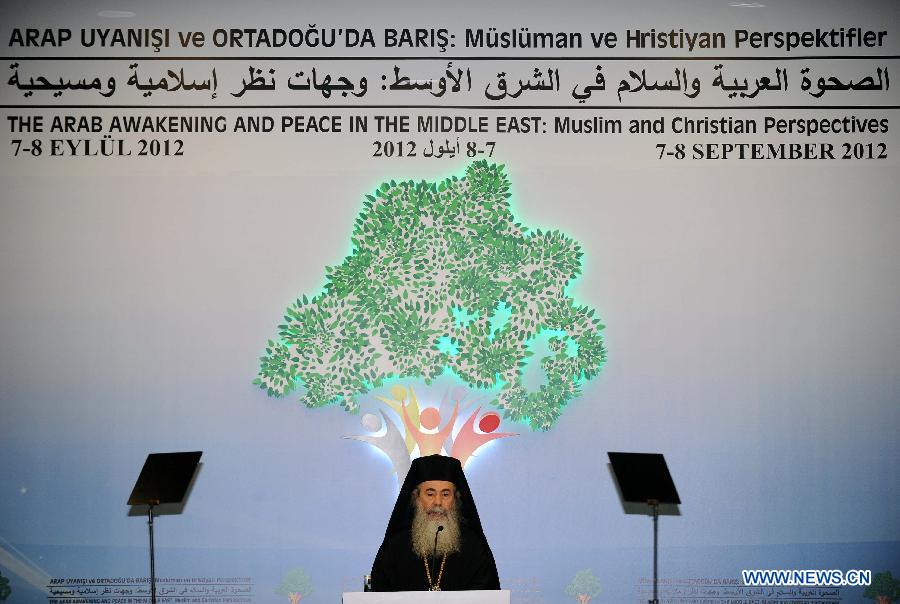

|

| Theofilos III, Patriarch of the Christian Orthodox Church in Jerusalem, addresses “The Arab Awakening and Peace in the New Middle East: Muslim and Christian Perspectives” at the international conference in Istanbul, Turkey, September 7, 2012. In many regards, most Christian speakers who attended the conference were less “reserved” than their Muslim peers in addressing the “survival” of Christianity in the Middle East. |

In the Middle East, any discussion of the future of the Christians must be seen as an approach to convince newly minted regional leaders—most of whom owe their titles to Islamist votes—of their real responsibility. In short, they must prove through the policies they enact and enforce that they are Muslims rather than Talibanis.

Turkey has indeed burst onto the regional, if not the international stage, within the last few years. In 2012 alone, Turkish PM Recep Tayyip Erdogan opened the first World Economic Forum on Middle East, North Africa and Eurasia, displayed commendable restraint in the face of Syrian military aggression and continues to weigh in on the sociopolitical challenges buffeting the Middle East. Perhaps in the spirit of the ancient “Council of Nicaea,” Turkey may aspire to chair an “Istanbul Council” that might reposition the Muslim Sunni creed to reflect the emerging “Turkish model.” After all, vis-à-vis its Islamic heritage, Turkey has long since learned the art of shelving existential considerations in order to accommodate itself with the modern world.

Ultimately, while the Syrian crisis may not have been the masthead for the September conference, it certainly informed a great deal of its purpose. So much so in fact, that one of the conference leaders, Dr. Mehmet Görmez, observed in a paper he submitted to the Center of Strategic Research for Turkey’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Shiite and Salafi encroachments… are seeking to undermine Turkey’s influence….” What, then, will be the next ideological Turkish export?

Kelly Stedem contributed to this article.

Print

Print Share

Share