April 3, 2013

The March 20 session of the ongoing trial of Sheikh Hassan Mchaymech marked the first time the Military Court permitted testimony to be given by witnesses, as the Sheikh’s son Reda Mchaymech, brother Abdul Karim Mchaymech and longtime friend Rafiq Tarhini were called before the court.

The substance of that testimony, however, was confined to questions surrounding Sheikh Mchaymech’s moral character and whether the witnesses knew anything about his “questionable” foreign contacts. The Sheikh’s lawyer, Antoine Nehmeh also introduced evidence associated with falsified phone bills presented previously by the prosecution. The original phone bills he submitted revealed a discrepancy between the list of calls provided originally by the prosecution, which alleged that Sheikh Mchaymech made a series of phone calls to “questionable” foreign numbers. The calls in question represent the bulk of the evidence against Sheikh Mchaymech.

While allowing any type of testimony marks a significant step forward in the case, the witnesses called and the questions they were asked can be considered halfhearted attempts by the court to collect meaningful information. Since the three witnesses provided information that was not strictly relevant to the case, their respective contributions were of limited value in the process of uncovering the truth. In keeping with its past performance, however, the court has yet to permit the defense to call witnesses who might provide testimony capable of exonerating the Sheikh.

Notably, Mr. Nehmeh submitted an official request to the court on March 5—more than two weeks before the March 20 session—which asked that a number of individuals be called to testify. The people named in the request could provide even greater background for the case and confirm several benchmarks that occurred along the deteriorating course of the relations between Sheikh Mchaymech and Hezbollah. That information is instrumental to understanding how the Sheikh could stand before the Lebanese Military Court and claim that he is being held as a prisoner of conscience. It also important to recall that Sheikh Mchaymech’s ordeal did not begin in Lebanon, but instead commenced with his mysterious disappearance in Syria on July 7, 2010—and was followed by a very delayed reappearance in Beirut on October 8, 2011.

Mr. Nehmeh identified the following individuals and asked that they be summoned by the court:

• The officers of ISF intelligence (Far’ al-Maalomat) who interrogated Sheikh Mchaymech upon “receiving” him from the Syrian authorities, namely Captain Milad al-Khoury and Lieutenant Rabih Francis.

• Sheikh Ali Damoush, the head of Hezbollah’s External Affairs Unit and a longtime friend of Sheikh Mchaymech. Sheikh Damoush received the original report prepared by Sheikh Mchaymech about the trip to Europe. In particular, he received information about the allegedly questionable trip to Germany.

• Colonel Ali Noureddine of the LAF’s intelligence organization. The colonel met with Sheikh Mchaymech after his attempted kidnapping in 1998 and “advised” him to “forget” about the incident for the sake of his security and that of his family. According to the Sheikh’s son, Reda Mchaymech, the attempted kidnapping began (classically) when several individuals arrived in a vehicle with darkly tinted windows and sought to convince Sheikh Hassan (in the middle of the night) to accompany them so that the Sheikh could officiate a wedding ceremony. Although the incident did not come to fruition, it certainly intimidated the Sheikh.

• Sayyed Muhammad Tarhini, who tried to mediate relations between Sheikh Mchaymech and Hezbollah following the attempted kidnapping in 1998.

• Wafiq Safa, a senior Hezbollah Intelligence Officer, for his role in the kidnapping attempt.

• Mustapha Badreddine, a senior Hezbollah Intelligence Officer, for his role in the kidnapping attempt.

• Sheikh Nabil Qaouk, a senior Hezbollah member, for his role in the kidnapping attempt.

Ultimately, Mr. Nehmeh’s request has become the most political component of the trial, as it is more than a mere judicial request. That intrinsic capability is extremely important since the next court date is expected to include sentencing—which the court would pass without having conducted a comprehensive presentation of evidence and therefore, a thorough review of the facts. In the case of Sheikh Mchaymech, the court is either completely uninterested in conducting a fair trial or is unable to do so without provoking the ire of Hezbollah. Yet if the Military Court indeed charges Sheikh Mchaymech in the next session, the action would finally give the defense something concrete to argue. In contrast to the Sheikh’s current state of legal limbo, Mr. Nehmeh could actually begin the appeals process.

At the end of the session, Prosecutor Sami Sader requested that the trial be postponed until April in order to review the testimonies presented; however, the session did not end with that postponement. When Mr. Nehmeh later reviewed the minutes of the session, he discovered that the court reporter had failed to note everything that transpired, including the request for witnesses, the court’s response and the justification given by the court in its reply.

In his capacity as the Sheikh’s legal representative, Mr. Nemeh petitioned the court March 28 for an Erratum Statement that would account for all of the missing elements. He requested that statement be added to the official transcript of the March 20 session and that the court reporter responsible for the omission be replaced. Intentional or not, this oversight indeed prompts questions about the transparency of the Military Court and the fairness of any judgment it might pronounce.

Finally, this session received a significant amount of Arabic press coverage in an-Nahar, al-Liwaa and al-Mustaqbal, which primarily described the proceedings and testimonies offered by the witnesses. In its March 25 edition, al-Liwaa published a second article related to the Erratum Statement Mr. Nehmeh submitted to the court.

.jpg) |

|

The list of names that the Sheikh's lawyer Antoine Nehmeh has requested that the Military Court call as witnesses.

|

The substance of that testimony, however, was confined to questions surrounding Sheikh Mchaymech’s moral character and whether the witnesses knew anything about his “questionable” foreign contacts. The Sheikh’s lawyer, Antoine Nehmeh also introduced evidence associated with falsified phone bills presented previously by the prosecution. The original phone bills he submitted revealed a discrepancy between the list of calls provided originally by the prosecution, which alleged that Sheikh Mchaymech made a series of phone calls to “questionable” foreign numbers. The calls in question represent the bulk of the evidence against Sheikh Mchaymech.

While allowing any type of testimony marks a significant step forward in the case, the witnesses called and the questions they were asked can be considered halfhearted attempts by the court to collect meaningful information. Since the three witnesses provided information that was not strictly relevant to the case, their respective contributions were of limited value in the process of uncovering the truth. In keeping with its past performance, however, the court has yet to permit the defense to call witnesses who might provide testimony capable of exonerating the Sheikh.

Notably, Mr. Nehmeh submitted an official request to the court on March 5—more than two weeks before the March 20 session—which asked that a number of individuals be called to testify. The people named in the request could provide even greater background for the case and confirm several benchmarks that occurred along the deteriorating course of the relations between Sheikh Mchaymech and Hezbollah. That information is instrumental to understanding how the Sheikh could stand before the Lebanese Military Court and claim that he is being held as a prisoner of conscience. It also important to recall that Sheikh Mchaymech’s ordeal did not begin in Lebanon, but instead commenced with his mysterious disappearance in Syria on July 7, 2010—and was followed by a very delayed reappearance in Beirut on October 8, 2011.

Mr. Nehmeh identified the following individuals and asked that they be summoned by the court:

• The officers of ISF intelligence (Far’ al-Maalomat) who interrogated Sheikh Mchaymech upon “receiving” him from the Syrian authorities, namely Captain Milad al-Khoury and Lieutenant Rabih Francis.

• Sheikh Ali Damoush, the head of Hezbollah’s External Affairs Unit and a longtime friend of Sheikh Mchaymech. Sheikh Damoush received the original report prepared by Sheikh Mchaymech about the trip to Europe. In particular, he received information about the allegedly questionable trip to Germany.

• Colonel Ali Noureddine of the LAF’s intelligence organization. The colonel met with Sheikh Mchaymech after his attempted kidnapping in 1998 and “advised” him to “forget” about the incident for the sake of his security and that of his family. According to the Sheikh’s son, Reda Mchaymech, the attempted kidnapping began (classically) when several individuals arrived in a vehicle with darkly tinted windows and sought to convince Sheikh Hassan (in the middle of the night) to accompany them so that the Sheikh could officiate a wedding ceremony. Although the incident did not come to fruition, it certainly intimidated the Sheikh.

• Sayyed Muhammad Tarhini, who tried to mediate relations between Sheikh Mchaymech and Hezbollah following the attempted kidnapping in 1998.

• Wafiq Safa, a senior Hezbollah Intelligence Officer, for his role in the kidnapping attempt.

• Mustapha Badreddine, a senior Hezbollah Intelligence Officer, for his role in the kidnapping attempt.

• Sheikh Nabil Qaouk, a senior Hezbollah member, for his role in the kidnapping attempt.

|

|

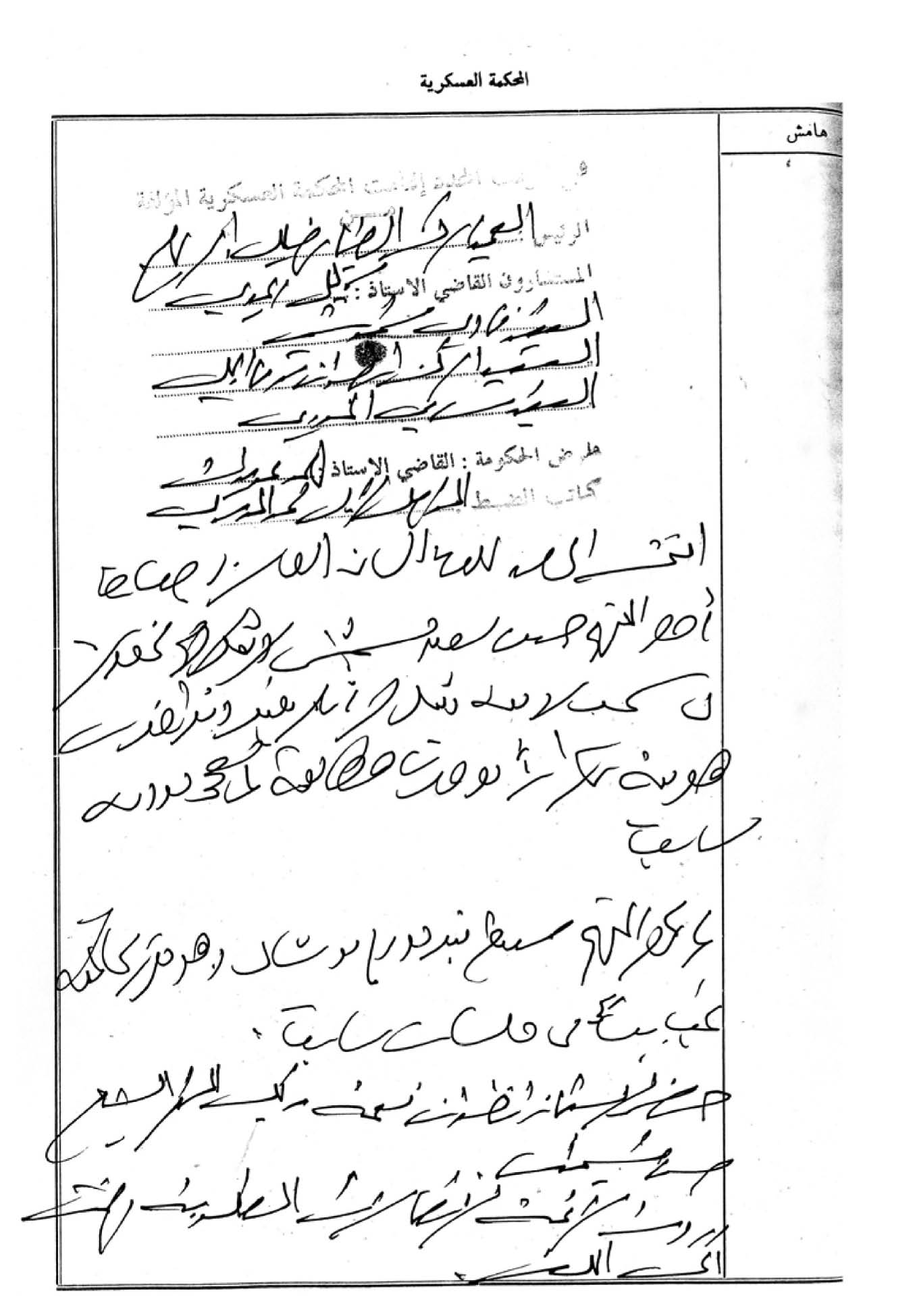

The first page of the handwritten minutes of the court session on March 20, 2013.

|

At the end of the session, Prosecutor Sami Sader requested that the trial be postponed until April in order to review the testimonies presented; however, the session did not end with that postponement. When Mr. Nehmeh later reviewed the minutes of the session, he discovered that the court reporter had failed to note everything that transpired, including the request for witnesses, the court’s response and the justification given by the court in its reply.

In his capacity as the Sheikh’s legal representative, Mr. Nemeh petitioned the court March 28 for an Erratum Statement that would account for all of the missing elements. He requested that statement be added to the official transcript of the March 20 session and that the court reporter responsible for the omission be replaced. Intentional or not, this oversight indeed prompts questions about the transparency of the Military Court and the fairness of any judgment it might pronounce.

Finally, this session received a significant amount of Arabic press coverage in an-Nahar, al-Liwaa and al-Mustaqbal, which primarily described the proceedings and testimonies offered by the witnesses. In its March 25 edition, al-Liwaa published a second article related to the Erratum Statement Mr. Nehmeh submitted to the court.

-----------------------------------------------------

Kelly Stedem contributed to this article

-----------------------------------------------------

Kelly Stedem contributed to this article

-----------------------------------------------------

Print

Print Share

Share