August 01, 2013

After years of deliberation, the European Union finally voted on July 22 to blacklist Hezbollah's so-called “military wing” after characterizing it as a terrorist organization. The debate over the existence of discrete "wings” within Hezbollah has remained remarkably byzantine (as have the anecdotes provoked by the wording of the decision), especially since Hezbollah’s upper-level leaders—from Hassan Nasrallah on down—have confirmed repeatedly that the organization is both completely integrated and virtually inseparable. In light of these starkly contrasting frames of reference, any effective analysis of the EU decision and its political implications must adopt a global perspective, which should not be confined to Lebanon per se or Hezbollah as a “component” of the overall Lebanese spectrum. The approach should address several aspects, including Lebanon’s future political power sharing, the persistent and unfolding conflict in Syria and the limits of tolerable Iranian influence in Lebanon and the Middle East.

By targeting its as yet undefined course of action against Hezbollah's patently fictitious military wing, the EU decision arbitrarily established a “category” which may—at least in the minds of those who voted—set the conditions of possibility that might encourage a broad range of outcomes. From the perspective of those who pushed all 28 EU countries to vote on this decision, these potential outcomes could run the gamut from triggering a redefinition of Hezbollah's internal dynamics among its supposedly “moderate” and “hard-line” decision makers, to a revision of the roles the organization plays on the Lebanese, regional and international scenes. Thus, among the EU members who voted, these supposed outcomes would be unlikely to succeed without first having created the “military wing” category and accusing that wing specifically of engaging in “terrorism.”

The complex motivation behind the action of the EU member states became apparent through the machinations of European diplomats and Hezbollah, which began after the announcement was made. The speech Hassan Nasrallah gave in response to the decision was neither particularly bellicose nor extreme when compared to the quintessential "scale of Nasrallah rhetoric." Of course, he stated that the EU would be considered a partner to any military action Israel may take against Lebanon since they “are making themselves complicit in Israeli aggressions against Lebanon and the Resistance.” At the same time, however, he essentially absolved the EU of any blame for the outcome of the vote by attributing its result to pressure exerted on the EU by the United States and Israel, adding, “The facts prove that the Israelis and the Americans exercised tremendous pressure on the European Union countries to take such a decision.” Another interesting aspect of Nasrallah's speech is that he cast the EU's decision as being related solely to the conflict between Hezbollah and Israel. Noticeably absent in that presentation was any mention of Syria, Iran, the Special Tribunal for Lebanon or even the terrorist acts for which Hezbollah still stands accused. The recent bombing of Israeli tourists in Bulgaria by alleged Hezbollah members, for example, was not mentioned once. Equally interesting is that other well-placed Hezbollah members who commented independently on the vote maintained Nasrallah's unique tone of "approachability."

Of course, the rather accommodating tone Nasrallah used in his speech can certainly be attributed to Hezbollah's desire to assert the notion of its own victimization by painting itself as the underdog versus the US-Zionist monolith, and now the EU behemoth. In general, Hezbollah’s response to the EU decision was characterized by the organization's “Lebanonization” of the accusation. That "spin" was intended not only to boost Hezbollah’s image as actively “resisting” (protecting the country from) any potential Israeli threats, but also to highlight the fact that any Lebanese attempt to challenge Hezbollah's interpretation of the EU decision was tantamount to an act of “treason.” Notably, Hezbollah employed the same logic after the 2006 War when it accused some Lebanese of having applauded Israel's military action. The EU decision thus could be "hijacked" by Hezbollah in order to intimidate Lebanese citizens who are critical of the organization's foreign "adventures," actions it justifies by declaring that Hezbollah itself had come under physical and philosophical attack. In notable contrast to Hezbollah's propaganda blitz, the EU took no action to blacklist the organization—as long as it remained focused on its original objective (“resistance”). In the face of such inherent latitude, then, the idea that the EU decision also increases the potential for Israeli aggression against Lebanon is entirely false.

After the vote was announced, the EU delegation ambassador to Lebanon Angelina Eichhorst met with the Lebanese president and other national officials and prominent politicians to explain the background of the EU vote. According to some very reliable leaks ShiaWatch received about that meeting, the various members of the Lebanese contingent were far more concerned about the impact the decision would have on the UNIFIL soldiers deployed to South Lebanon per UNSCR 1701 than were the EU representatives. That concern seems to insulate a strange reversal of roles between the Lebanese and the EU and may lie at the heart of this contentious decision. However, Hezbollah and its Iranian patron likely see the EU's decision as part of a larger game, an endurable action that does not seem "foul" in any sense.

Regardless of the anticipation being shown by some Lebanese about the EU's decision and the hope they invest in its ability to change the course of events on the country's domestic scene, the decision is intended generally as a message to the Iranian regime via its Lebanese factotum. As such, it should be viewed as the next effort in the confusing, often contradictory exchange of communications between Iran and the Western members of "5+1" group. In keeping with that perspective, it was certainly not serendipitous when the director general of Lebanese General Security—a state security apparatus fully controlled by Hezbollah—arrived at UNIFIL headquarters to deliver a “conciliatory” message just a day after the vote was announced. That same day, Eichhorst stated during a meeting with Hezbollah foreign affairs spokesperson Ammar al-Musawi that “dialogue continues between the European Union and all Lebanese political parties, including Hezbollah.” This statement, while seemingly benign, also demonstrates the EU's willingness to play directly into the hands of Lebanon’s sectarianism.

Ultimately, it is important to note that the bureaucratic ambiguity of the EU's decision enhances its overall flexibility and adaptability. With the EU having separated Hezbollah’s activities into separate branches, it gives Hezbollah a “grace period” in which to maintain two separate spheres of engagement: maintaining contact with European diplomats and decision makers while it continues to pursue the same activities characterized by the EU vote as acts of terrorism. But that vote also offers Hezbollah an acceptable exit strategy. The EU's employment of diplomatic sleight of hand to divide Hezbollah into discrete wings essentially gives the organization a means with which to undue its past “offenses.” It also appears that many EU member states believe that by adding pressure to Hezbollah's military "wing," some benefit could accrue to the organization's political entities. According to al-Jazeera, some EU diplomats are of the opinion that the decision may ultimately “persuade some of its members to move away from violence into the political sphere.” In general, this idea derives from the notion that by pressuring Hezbollah, some space would be opened to allow the advancement of increasingly moderate elements. Unfortunately, that approach ignores the reality that change cannot be realized from within Hezbollah's internal mechanisms. Rather, it must originate with the Lebanon's Shia community itself by capitalizing on its exclusivity from that organization.

Based on the precedent set by the EU, it is likely that an increasing number of countries will make similar decisions. On July 17, the Arab Gulf countries agreed to blacklist Hezbollah—in full—as a terrorist group and are now wrangling over how the decision should be implemented. The announcement followed the efforts made previously by several Gulf Cooperation Council states to deport Lebanese (Shia) citizens accused of aiding Hezbollah. While such punitive actions have been occurring at least since 2009, they increased markedly after Hezbollah announced its engagement in the Syrian conflict. Yet many of the Lebanese who have been deported contest the actions as being inspired by sectarianism: "Not every Shiite is Hezbollah."

Now that the EU’s decision has been announced, the Lebanese must face the inevitable question: What's next? In fact, the EU's action offers the Lebanese a unique opportunity to review their own political conditions and determine for themselves how they should respond. Three logical responses seem immediately apparent.

First, The Lebanese will fall in line with Hezbollah and uphold the organization’s allegations that a US-Israeli conspiracy influenced the outcome of the vote. We have already seen criticism of the decision by a number of influential individuals, from President Suleiman to Speaker Nabih Berri. Former Prime Minister Najib Mikati also came to Hezbollah's defense on July 24 when he claimed, “Lebanon’s respect for international legitimacy underscores its right to resistance according to article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations.”

Second, they will accept the intent of the EU’s decision and recognize that others are taking a stance against Hezbollah. In either case, rather than moving beyond the ideological duels that have taken hold of the country during the past decade, the Lebanese would likely become even further entrenched in the country's political stalemate.

Finally, the Lebanese may see this outcome as an opportunity to reconsider Lebanon's political situation thoroughly. Clearly, the fact that the EU, a major international entity now considers Hezbollah (or at least some part of it) a terrorist organization—despite the fact that Hezbollah's constituency is comprised of a significant percentage of the population—is indeed worthy of consideration. In this sense, the EU’s decision has introduced the possibility of dialogue and substantive discussions within Lebanon's Shia community and indeed throughout the country regarding the nation's present political conditions and the future the Lebanese jointly hope to create.

|

|

| The official EU press release which announced that Hezbollah's "military wing" had been designated a terrorist organization. | |

By targeting its as yet undefined course of action against Hezbollah's patently fictitious military wing, the EU decision arbitrarily established a “category” which may—at least in the minds of those who voted—set the conditions of possibility that might encourage a broad range of outcomes. From the perspective of those who pushed all 28 EU countries to vote on this decision, these potential outcomes could run the gamut from triggering a redefinition of Hezbollah's internal dynamics among its supposedly “moderate” and “hard-line” decision makers, to a revision of the roles the organization plays on the Lebanese, regional and international scenes. Thus, among the EU members who voted, these supposed outcomes would be unlikely to succeed without first having created the “military wing” category and accusing that wing specifically of engaging in “terrorism.”

The complex motivation behind the action of the EU member states became apparent through the machinations of European diplomats and Hezbollah, which began after the announcement was made. The speech Hassan Nasrallah gave in response to the decision was neither particularly bellicose nor extreme when compared to the quintessential "scale of Nasrallah rhetoric." Of course, he stated that the EU would be considered a partner to any military action Israel may take against Lebanon since they “are making themselves complicit in Israeli aggressions against Lebanon and the Resistance.” At the same time, however, he essentially absolved the EU of any blame for the outcome of the vote by attributing its result to pressure exerted on the EU by the United States and Israel, adding, “The facts prove that the Israelis and the Americans exercised tremendous pressure on the European Union countries to take such a decision.” Another interesting aspect of Nasrallah's speech is that he cast the EU's decision as being related solely to the conflict between Hezbollah and Israel. Noticeably absent in that presentation was any mention of Syria, Iran, the Special Tribunal for Lebanon or even the terrorist acts for which Hezbollah still stands accused. The recent bombing of Israeli tourists in Bulgaria by alleged Hezbollah members, for example, was not mentioned once. Equally interesting is that other well-placed Hezbollah members who commented independently on the vote maintained Nasrallah's unique tone of "approachability."

Of course, the rather accommodating tone Nasrallah used in his speech can certainly be attributed to Hezbollah's desire to assert the notion of its own victimization by painting itself as the underdog versus the US-Zionist monolith, and now the EU behemoth. In general, Hezbollah’s response to the EU decision was characterized by the organization's “Lebanonization” of the accusation. That "spin" was intended not only to boost Hezbollah’s image as actively “resisting” (protecting the country from) any potential Israeli threats, but also to highlight the fact that any Lebanese attempt to challenge Hezbollah's interpretation of the EU decision was tantamount to an act of “treason.” Notably, Hezbollah employed the same logic after the 2006 War when it accused some Lebanese of having applauded Israel's military action. The EU decision thus could be "hijacked" by Hezbollah in order to intimidate Lebanese citizens who are critical of the organization's foreign "adventures," actions it justifies by declaring that Hezbollah itself had come under physical and philosophical attack. In notable contrast to Hezbollah's propaganda blitz, the EU took no action to blacklist the organization—as long as it remained focused on its original objective (“resistance”). In the face of such inherent latitude, then, the idea that the EU decision also increases the potential for Israeli aggression against Lebanon is entirely false.

|

|

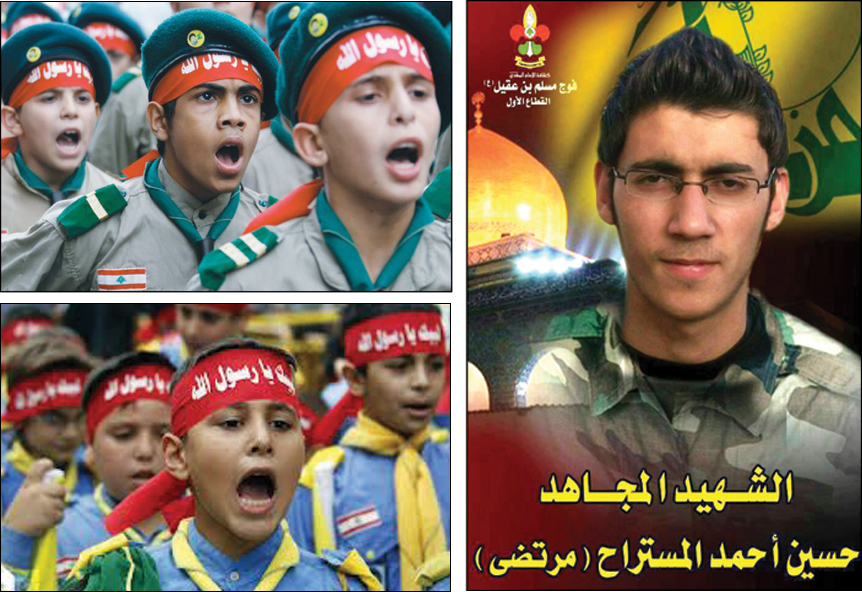

| Left, a group of al-Mahdi “cubs” during a march. Right, a “scout” who ultimately became a fallen “shaheed” in Syria. The background of the photo includes the Hezbollah flag and the scout logo. |

|

|

“The formation of the Imam Al-Mahdi Scouts in 1985 is a testament to Hezbollah’s vision of a protracted war. The Scouts are a youth movement intended to indoctrinate the younger generations…. Ultimately, the program provides a steady stream of recruits and increases their support base. The scouts range in age from 8 to 16 and are transferred to the military wing at the age of 17. They participate in traditional scouting activities like camping trips, play sports and assist charities; [however,] Hezbollah indoctrination is included in every activity.”

James B. Love. "Hezbollah: Social Services as a Source of Power." JSOU Report 10-5. June 2010. |

|

Regardless of the anticipation being shown by some Lebanese about the EU's decision and the hope they invest in its ability to change the course of events on the country's domestic scene, the decision is intended generally as a message to the Iranian regime via its Lebanese factotum. As such, it should be viewed as the next effort in the confusing, often contradictory exchange of communications between Iran and the Western members of "5+1" group. In keeping with that perspective, it was certainly not serendipitous when the director general of Lebanese General Security—a state security apparatus fully controlled by Hezbollah—arrived at UNIFIL headquarters to deliver a “conciliatory” message just a day after the vote was announced. That same day, Eichhorst stated during a meeting with Hezbollah foreign affairs spokesperson Ammar al-Musawi that “dialogue continues between the European Union and all Lebanese political parties, including Hezbollah.” This statement, while seemingly benign, also demonstrates the EU's willingness to play directly into the hands of Lebanon’s sectarianism.

Ultimately, it is important to note that the bureaucratic ambiguity of the EU's decision enhances its overall flexibility and adaptability. With the EU having separated Hezbollah’s activities into separate branches, it gives Hezbollah a “grace period” in which to maintain two separate spheres of engagement: maintaining contact with European diplomats and decision makers while it continues to pursue the same activities characterized by the EU vote as acts of terrorism. But that vote also offers Hezbollah an acceptable exit strategy. The EU's employment of diplomatic sleight of hand to divide Hezbollah into discrete wings essentially gives the organization a means with which to undue its past “offenses.” It also appears that many EU member states believe that by adding pressure to Hezbollah's military "wing," some benefit could accrue to the organization's political entities. According to al-Jazeera, some EU diplomats are of the opinion that the decision may ultimately “persuade some of its members to move away from violence into the political sphere.” In general, this idea derives from the notion that by pressuring Hezbollah, some space would be opened to allow the advancement of increasingly moderate elements. Unfortunately, that approach ignores the reality that change cannot be realized from within Hezbollah's internal mechanisms. Rather, it must originate with the Lebanon's Shia community itself by capitalizing on its exclusivity from that organization.

Based on the precedent set by the EU, it is likely that an increasing number of countries will make similar decisions. On July 17, the Arab Gulf countries agreed to blacklist Hezbollah—in full—as a terrorist group and are now wrangling over how the decision should be implemented. The announcement followed the efforts made previously by several Gulf Cooperation Council states to deport Lebanese (Shia) citizens accused of aiding Hezbollah. While such punitive actions have been occurring at least since 2009, they increased markedly after Hezbollah announced its engagement in the Syrian conflict. Yet many of the Lebanese who have been deported contest the actions as being inspired by sectarianism: "Not every Shiite is Hezbollah."

Now that the EU’s decision has been announced, the Lebanese must face the inevitable question: What's next? In fact, the EU's action offers the Lebanese a unique opportunity to review their own political conditions and determine for themselves how they should respond. Three logical responses seem immediately apparent.

|

|

| In 2010, a group of some 30 women sympathetic to Hezbollah made headlines after attacking investigators from the UN’s Special Tribunal for Lebanon, an investigation that would later implicate Hezbollah members for the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri. The incident allegedly began when a number of women accosted two STL investigators and their translator as they were attempting to interview Dr. Iman Charara at her gynecology clinic in Dahiyeh. A briefcase believed to have contained a list of witnesses was taken from the investigators during the incident and was leaked by al-Akhbar newspaper in 2013. |

Second, they will accept the intent of the EU’s decision and recognize that others are taking a stance against Hezbollah. In either case, rather than moving beyond the ideological duels that have taken hold of the country during the past decade, the Lebanese would likely become even further entrenched in the country's political stalemate.

Finally, the Lebanese may see this outcome as an opportunity to reconsider Lebanon's political situation thoroughly. Clearly, the fact that the EU, a major international entity now considers Hezbollah (or at least some part of it) a terrorist organization—despite the fact that Hezbollah's constituency is comprised of a significant percentage of the population—is indeed worthy of consideration. In this sense, the EU’s decision has introduced the possibility of dialogue and substantive discussions within Lebanon's Shia community and indeed throughout the country regarding the nation's present political conditions and the future the Lebanese jointly hope to create.

-----------------------------------------------------

Kelly Stedem contributed to this article

-----------------------------------------------------

Kelly Stedem contributed to this article

-----------------------------------------------------

Print

Print Share

Share