November 22, 2013

[In the early 1980s,] several special security groups were established [in Lebanon], and [they quickly gained] weight and effectiveness. Within a [relatively] short period, [those groups] proved their skills in protecting the Islamic Line. They represented the military arm needed by that Line to protect its various formations, which were rooting themselves into a country where [virtually] any political presence [must have] a parallel military presence. The spring 1981 bombing of the Iraqi Embassy in Ramlet al-Bayda—by way of a booby-trapped car driven by Iraqi Abou Maryam—gave a new impetus to that Islamic current….

The conclusion to the lines above, excerpted from one of the first “self-historiographic” essays to focus on Hezbollah (“The Other Choice: Hezbollah – Autobiography and Stands”), prompt one to consider that a successful terrorist attack against a diplomatic facility can be justified for having produced a desirable boost in a creeping ideological trend. At the time the book was published, its author, Hassan Fadlallah, was an anonymous, young Hezbollah militant and intellectual. But since 2009, he has been a member of the Lebanese Parliament representing Hezbollah's “Loyalty to the Resistance” bloc.

To someone who has observed the Lebanese scene over the long term, H. Fadlallah's description of Hezbollah's early days still seems remarkably contemporary and relevant to the Byzantine debate over the nature of Hezbollah in terms of its political and military presence. In fact, the same words that can be used to characterize the 1981 attack on the Iraqi Embassy could be applied mutadis mutandis to describe the pair of bombings that targeted the Iranian Embassy in Beirut on November 19. Beyond causing the deaths of more than two dozen people, wounding scores more and producing massive destruction, the coordinated attack introduces a substantial yet general question relative to the course of political and security developments in Lebanon and beyond. At the same time, it prompts examination of a possible shift in Lebanon’s function from a jihadi “land of support” (or ard nusra, an area kept clear of military operations in order to sustain those on the battlefield) to a land of jihad (ard jihad).

To be precise, the attack that devastated the Iraqi Embassy in 1981 was conducted under vastly different circumstances. At the time, Saddam Hussein's Iraq was locked in protracted combat against its once Sunniruled neighbor, a state that had been the darling of the Gulf States and the West. But Iran had changed dramatically. At the time One Embassy for Another... Examining the Twist in This Drama of the conflict, it was a very young Islamic Republic led by its first Supreme Leader/ founder Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Its engagement against Iraq, a historical Arab enemy, advanced Iran's antagonism of the Arab world (with the notable exceptions of Syria and Algeria) while it sought to solidify its domestic foundation and export its brand of revolution to the farthest corners of the region.

By consulting the events of the last three decades, one can draw any number of comparisons between the region's past and present landscape. Despite the many sociopolitical changes that impacted the Middle East during that time, three significant factors deserve mention. First, the Iran-Iraq War produced a politically militant form of Shi'ism, which deepened Shia- Sunni political fault lines. Those rifts were nourished over time by deep-seated hatred and ancient theological (and sometimes mythological) arguments. Second, the al- Assads' Alawi regime in Syria (beginning with Hafez al-Assad and inherited by his son Bashar) played a pivotal role by serving intermittently as Iran's hidden door to the Arab world—and at other times as its Trojan horse. Third, Lebanon itself—and later via Hezbollah—played a vital part in this danse macabre by becoming a wild card in Iran's overall strategy.

In reality, none of these three features has lost any importance in the decades that have followed. On the contrary, the topography of Sunni-Shia hostilities has expanded thanks in part to concerted proselytism, investments that have been made in sectarian mobilization by the respective Sunni and Shia poles (i.e., Saudi Arabia and Iran, respectively) and an ensuing rise in tensions between the two. In spring 2011, Syria became the most recent battlefield to host the enduring competition between Iran and Saudi Arabia, the most persistent characteristic of which has been steadily increasing Sunni-Shia/Alawi violence. Iran and Saudi Arabia continue to give the world the impression that in Syria, they are fighting a decisive battle, the outcome of which will extend far beyond Syria's borders. As a result and apart from Saudi Arabia and Iran per se, all involved have adjusted their positions on the conflict as evidenced by the waxing and waning of support and interest. Hezbollah, on the other hand, simply continues to offer nauseatingly tedious descriptions of the various roles it plays in favor of Iranian policies and global strategy in Lebanon, Syria and beyond.

Based on the foregoing, it is indeed intriguing to review the history of the al-Qaeda affiliated Abdullah Azzam Brigades, which claimed responsibility for the November 19 attack. As well, it is interesting to profile Lebanese Sheikh Siraj ed-Din Zureikat (the organization's current leader) and consider the veracity of his comments on the attack. Specifically, Zureikat asserted that the two suicide bombers were “young Lebanese Sunni,” which contradicts the image being crafted carefully by the Syrian regime and Hezbollah that jihadi Islamists are not “indigenous” to Syria or Lebanon and are therefore “imported.” We should also be aware of other issues tangential to the attack, such as the mood of Lebanon's Shia community in general and that of Hezbollah's constituency in particular. After all, this decisive breach of “Shia” security runs demonstrably counter to today's propaganda, which holds that Hezbollah's involvement in Syria facilitates its protection of its constituents at home.

Clearly, these are just a few of the challenging questions that must be asked, all of which deserve prudent and well-researched responses. Ultimately, however, the fundamental question to be asked about the deadly November 19 bombing is what changed? What elements in the convoluted, threedecade- long escalation and diminishment of hostilities created the conditions that were ripe for this aggression? Compared to previous rocket and car bomb attacks against “anonymous” targets, what happened to open the door for a direct attack against Tehran conducted in the heart of Beirut's Dahyeh area?

A key to answering this multifaceted question can perhaps be found in the swift Iranian accusation of “the Zionist entity”—with the notable exclusion of the US which is typically associated with that so-called “entity”—as having been behind the double bombing. As opined by many (including pro-Hezbollah) observers, the accusation is entirely “ideological” in nature and was aimed at giving Tehran more time and greater maneuverability, both of which it needs to manage its regional challenges. The most problematic of Iran's threats is represented by the Sunni Arab world, which is headed by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and while Iranian officials decline to address the matter directly, it has been confirmed repeatedly by other pro-Iranian allies and spokesmen. In the hours following the bombing, Syria's minister of information said, “What happened is not a spontaneous act. Saudi and Israeli intelligence stand behind it.” The next day, al-Akhbar's editor in-chief published a story that linked the bombing to the failed March 8, 1985 attack on Sayyed Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah that was “carried out by local CIA operatives and financed by Saudi Arabia by way of the kingdom's ambassador in Washington, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, who now headsthe country's intelligence services.”

Quite clearly, no one is claiming to be naïve about the extent of the ongoing confrontation. While transiting Beirut recently, a senior Saudi official told ShiaWatch:

Tehran may or may not reach provisional agreement on its nuclear programs, and it may or may not enjoy some relief from the sanctions that have been imposed by world powers— impediments that will at least in the short term produce [some] very limited effects…. [The enduring tensions between Tehran and us have changed the very nature of the stakes [involved and]…before anything else, we need to agree again on what we [decided originally to] disagree about….

Regardless of who masterminded, funded and coordinated the November 19 attack against the Iranian Embassy in Beirut, those who claimed responsibility for that outrage took pains to title it in a fashion reminiscent of other al-Qaeda attacks. Thus, the November 19 “Raid of Beirut” followed the examples of the “Great Raid of New York” (September 11, 2001), the “Raid of Madrid” (the March 11, 2004 train bombings) and the “Raid of London” (the bombings that took place on July 7, 2005). From the perpetrators' perspective, this most recent attack has already become part of an ongoing history of similar events…and no one can claim a “copyright” on history, as it falls within the parameters identified as “Creative Commons.”

Although the outcome of the November 19 attack may pale in comparison to other embassy bombings conducted in Lebanon during the last several decades, this one is vastly different. Realists and pragmatists should consider the attack a turning point in a longstanding conflict. We should also understand that the actors involved, major and minor alike, will do their best to capitalize on this new “history” directly or indirectly.

[In the early 1980s,] several special security groups were established [in Lebanon], and [they quickly gained] weight and effectiveness. Within a [relatively] short period, [those groups] proved their skills in protecting the Islamic Line. They represented the military arm needed by that Line to protect its various formations, which were rooting themselves into a country where [virtually] any political presence [must have] a parallel military presence. The spring 1981 bombing of the Iraqi Embassy in Ramlet al-Bayda—by way of a booby-trapped car driven by Iraqi Abou Maryam—gave a new impetus to that Islamic current….

|

|

|

|

|

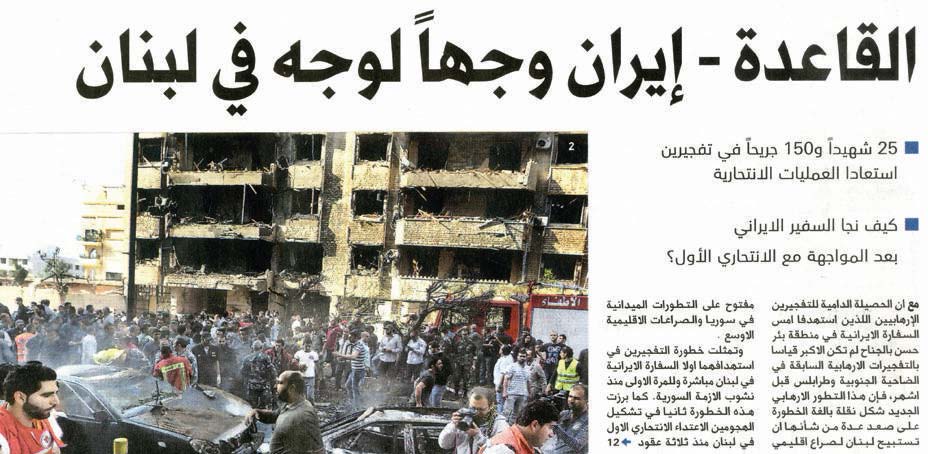

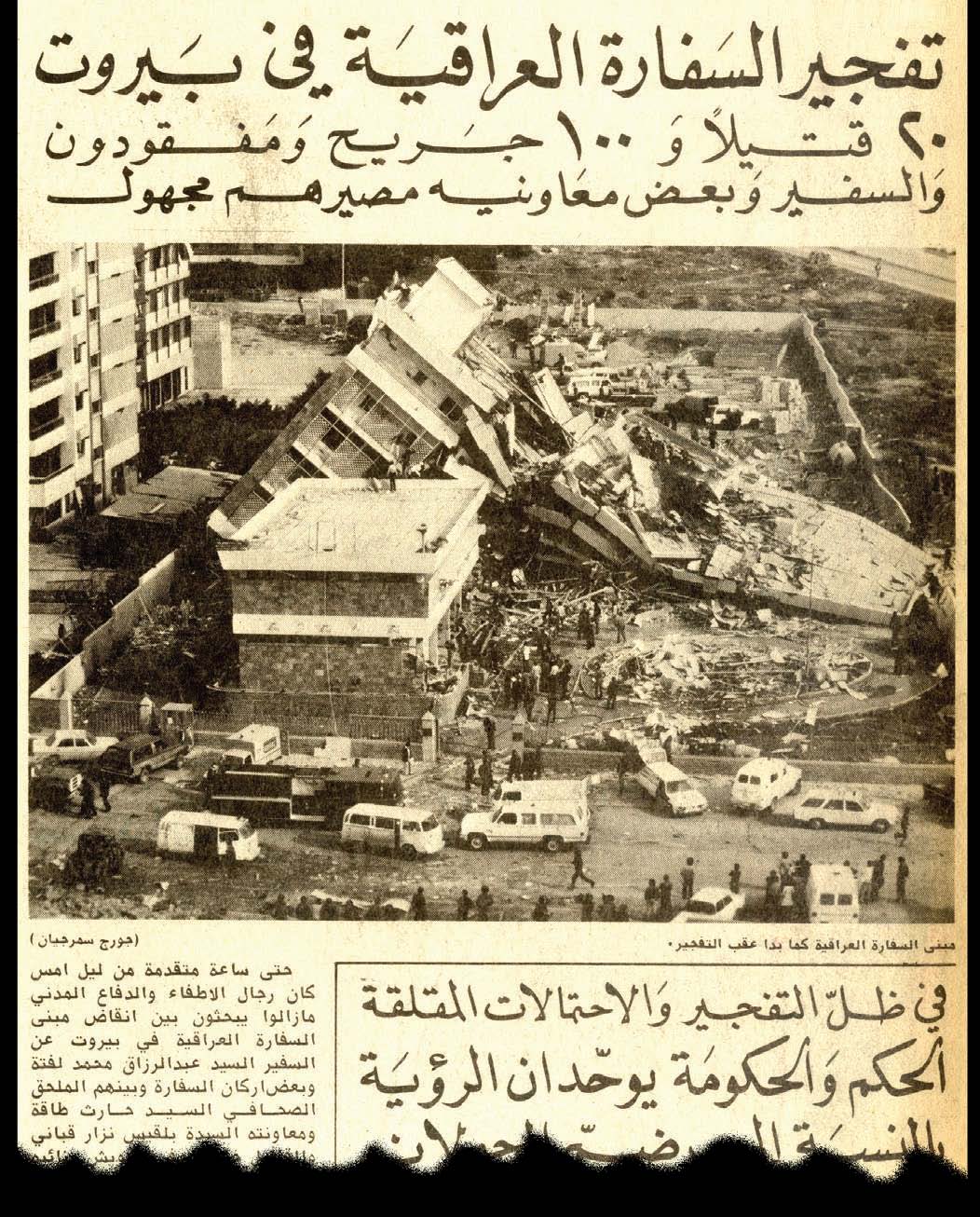

The front page of an-Nahar's December 16, 1981 issue. The headline reads "Bombing of the Iraqi Embassy in Beirut – 20 killed, 100 wounded and [several] missing – fate of the Iraqi ambassador and some of his aids unknown." In reality, the attack on the Iraqi Embassy did not come as a complete surprise. Rather, it occurred within the context of reciprocal violence between pro-Iraqi Baathist groups and those loyal to Khomeini. Beyond trading assassinations, the violence included direct clashes between the security elements attached to the Iraqi Embassy and a neighboring Iranian facility, which came to be known in the Lebanese vernacular as “The War of the Embassies.” The first widespread “political cleansing” campaigns that took place within the Lebanese Shia community (led by the predecessor to Hezbollah’s security apparatuses— the “special security groups” mentioned in the introductory excerpt) can be traced to that conflict. In comparison, the headline run by an Nahar on November 20, 2013 was far more ominous: “Al-Qaeda-Iran faceto- face in Lebanon.” The lede that followed read “25 martyrs and 150 wounded in two blasts [that reintroduced] suicide operations. How did the Iranian ambassador escape after colliding with the first suicide bomber?” In a sign of the times, it is interesting to note that those killed in the attack were referred to as “martyrs.”

|

To someone who has observed the Lebanese scene over the long term, H. Fadlallah's description of Hezbollah's early days still seems remarkably contemporary and relevant to the Byzantine debate over the nature of Hezbollah in terms of its political and military presence. In fact, the same words that can be used to characterize the 1981 attack on the Iraqi Embassy could be applied mutadis mutandis to describe the pair of bombings that targeted the Iranian Embassy in Beirut on November 19. Beyond causing the deaths of more than two dozen people, wounding scores more and producing massive destruction, the coordinated attack introduces a substantial yet general question relative to the course of political and security developments in Lebanon and beyond. At the same time, it prompts examination of a possible shift in Lebanon’s function from a jihadi “land of support” (or ard nusra, an area kept clear of military operations in order to sustain those on the battlefield) to a land of jihad (ard jihad).

To be precise, the attack that devastated the Iraqi Embassy in 1981 was conducted under vastly different circumstances. At the time, Saddam Hussein's Iraq was locked in protracted combat against its once Sunniruled neighbor, a state that had been the darling of the Gulf States and the West. But Iran had changed dramatically. At the time One Embassy for Another... Examining the Twist in This Drama of the conflict, it was a very young Islamic Republic led by its first Supreme Leader/ founder Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Its engagement against Iraq, a historical Arab enemy, advanced Iran's antagonism of the Arab world (with the notable exceptions of Syria and Algeria) while it sought to solidify its domestic foundation and export its brand of revolution to the farthest corners of the region.

By consulting the events of the last three decades, one can draw any number of comparisons between the region's past and present landscape. Despite the many sociopolitical changes that impacted the Middle East during that time, three significant factors deserve mention. First, the Iran-Iraq War produced a politically militant form of Shi'ism, which deepened Shia- Sunni political fault lines. Those rifts were nourished over time by deep-seated hatred and ancient theological (and sometimes mythological) arguments. Second, the al- Assads' Alawi regime in Syria (beginning with Hafez al-Assad and inherited by his son Bashar) played a pivotal role by serving intermittently as Iran's hidden door to the Arab world—and at other times as its Trojan horse. Third, Lebanon itself—and later via Hezbollah—played a vital part in this danse macabre by becoming a wild card in Iran's overall strategy.

In reality, none of these three features has lost any importance in the decades that have followed. On the contrary, the topography of Sunni-Shia hostilities has expanded thanks in part to concerted proselytism, investments that have been made in sectarian mobilization by the respective Sunni and Shia poles (i.e., Saudi Arabia and Iran, respectively) and an ensuing rise in tensions between the two. In spring 2011, Syria became the most recent battlefield to host the enduring competition between Iran and Saudi Arabia, the most persistent characteristic of which has been steadily increasing Sunni-Shia/Alawi violence. Iran and Saudi Arabia continue to give the world the impression that in Syria, they are fighting a decisive battle, the outcome of which will extend far beyond Syria's borders. As a result and apart from Saudi Arabia and Iran per se, all involved have adjusted their positions on the conflict as evidenced by the waxing and waning of support and interest. Hezbollah, on the other hand, simply continues to offer nauseatingly tedious descriptions of the various roles it plays in favor of Iranian policies and global strategy in Lebanon, Syria and beyond.

Based on the foregoing, it is indeed intriguing to review the history of the al-Qaeda affiliated Abdullah Azzam Brigades, which claimed responsibility for the November 19 attack. As well, it is interesting to profile Lebanese Sheikh Siraj ed-Din Zureikat (the organization's current leader) and consider the veracity of his comments on the attack. Specifically, Zureikat asserted that the two suicide bombers were “young Lebanese Sunni,” which contradicts the image being crafted carefully by the Syrian regime and Hezbollah that jihadi Islamists are not “indigenous” to Syria or Lebanon and are therefore “imported.” We should also be aware of other issues tangential to the attack, such as the mood of Lebanon's Shia community in general and that of Hezbollah's constituency in particular. After all, this decisive breach of “Shia” security runs demonstrably counter to today's propaganda, which holds that Hezbollah's involvement in Syria facilitates its protection of its constituents at home.

Clearly, these are just a few of the challenging questions that must be asked, all of which deserve prudent and well-researched responses. Ultimately, however, the fundamental question to be asked about the deadly November 19 bombing is what changed? What elements in the convoluted, threedecade- long escalation and diminishment of hostilities created the conditions that were ripe for this aggression? Compared to previous rocket and car bomb attacks against “anonymous” targets, what happened to open the door for a direct attack against Tehran conducted in the heart of Beirut's Dahyeh area?

|

|

|

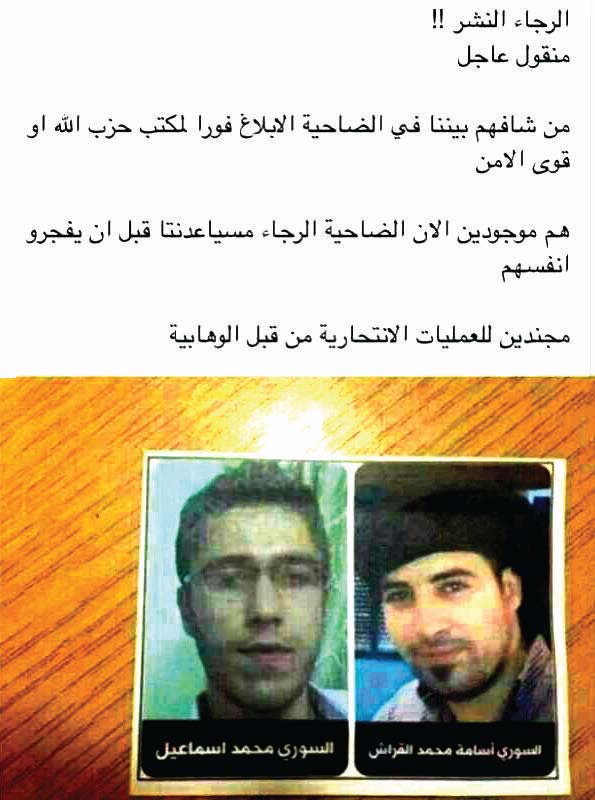

Several hours after the November 19 bombing, the message (above) began circulating on social media sites, phones and eventually as photocopied leaflets. The text reads:

Please disseminate. Urgent! Anyone who sees [these two individuals] among us in Dahyeh must immediately notify Hezbollah or the Lebanese security. [They] are in Dahyeh [and have been] enlisted by Wahhabism to conduct suicide operations. Please help us [spot them] before they explode themselves. Despite the substantial casualties caused by the November 19 bombings, Hezbollah's media outlets continue to describe the attack on the Iranian embassy as a “failed attempt.”* According to those sources, the bombers were unable to gain entry into the compound, which allegedly was their primary objective. |

A key to answering this multifaceted question can perhaps be found in the swift Iranian accusation of “the Zionist entity”—with the notable exclusion of the US which is typically associated with that so-called “entity”—as having been behind the double bombing. As opined by many (including pro-Hezbollah) observers, the accusation is entirely “ideological” in nature and was aimed at giving Tehran more time and greater maneuverability, both of which it needs to manage its regional challenges. The most problematic of Iran's threats is represented by the Sunni Arab world, which is headed by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and while Iranian officials decline to address the matter directly, it has been confirmed repeatedly by other pro-Iranian allies and spokesmen. In the hours following the bombing, Syria's minister of information said, “What happened is not a spontaneous act. Saudi and Israeli intelligence stand behind it.” The next day, al-Akhbar's editor in-chief published a story that linked the bombing to the failed March 8, 1985 attack on Sayyed Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah that was “carried out by local CIA operatives and financed by Saudi Arabia by way of the kingdom's ambassador in Washington, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, who now headsthe country's intelligence services.”

Quite clearly, no one is claiming to be naïve about the extent of the ongoing confrontation. While transiting Beirut recently, a senior Saudi official told ShiaWatch:

Tehran may or may not reach provisional agreement on its nuclear programs, and it may or may not enjoy some relief from the sanctions that have been imposed by world powers— impediments that will at least in the short term produce [some] very limited effects…. [The enduring tensions between Tehran and us have changed the very nature of the stakes [involved and]…before anything else, we need to agree again on what we [decided originally to] disagree about….

Regardless of who masterminded, funded and coordinated the November 19 attack against the Iranian Embassy in Beirut, those who claimed responsibility for that outrage took pains to title it in a fashion reminiscent of other al-Qaeda attacks. Thus, the November 19 “Raid of Beirut” followed the examples of the “Great Raid of New York” (September 11, 2001), the “Raid of Madrid” (the March 11, 2004 train bombings) and the “Raid of London” (the bombings that took place on July 7, 2005). From the perpetrators' perspective, this most recent attack has already become part of an ongoing history of similar events…and no one can claim a “copyright” on history, as it falls within the parameters identified as “Creative Commons.”

Although the outcome of the November 19 attack may pale in comparison to other embassy bombings conducted in Lebanon during the last several decades, this one is vastly different. Realists and pragmatists should consider the attack a turning point in a longstanding conflict. We should also understand that the actors involved, major and minor alike, will do their best to capitalize on this new “history” directly or indirectly.

Print

Print Share

Share