December 31, 2013

Throughout 2013, the ephemeral concept of "stability" for Lebanon remained the primary preoccupation for everyone with an interest in the country. Over time, the word evolved into a mantra chanted ad nauseam by local politicians as well as foreign diplomats, even though the definition they ascribe to the concept varies according to the individual concerned. While the evolving situation in the country increasingly produces scenes of sanguine violence, and despite the ongoing stalemate over the formation of a new government or holding the scheduled elections (a cumulative situation easily described as a political crisis), it may be useful to look beyond the indicators typically associated with security and stability to assess Lebanon’s current state. In that sense, the final month of 2013 proved particularly interesting in that beyond the issue of stability alone, many of Lebanon’s most enduring partisan vs. nonpartisan “myths” were laid bare. The text that follows will describe some manifestations of the deep fissures that have indeed affected Lebanon and are unlikely to be resolved simply through political decisions.

When Ziad Rahbany, the son of Lebanon's famous diva Fairuz (referred to as as-Sayyida Fairuz or Lady Fairuz by her adoring fans) was interviewed by the al-Ahed website, he mentioned—among other things—that his mother likes Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah.

That statement triggered a wave of comments, both supportive and derogatory. In response, particularly to the negative impressions, Ziad Rahbany appeared the following day on al-Mayadeen TV and stated that any Lebanese who liked neither Fairuz nor Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah was an Israeli sympathizer. In order to understand the magnitude of this disclosure, one must first recognize that among Lebanon's icons, Fairuz epitomizes the notion of good over evil, nurturing mother versus lady of the night; someone who is consistently discerning rather than neglectful. Notably, those involved in this complex chain of actions and reactions were by no means random users of Facebook and Twitter. For instance, Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, historian Fawwaz Traboulsi and even Hassan Nasrallah became involved, which propelled the matter to the forefront of Lebanese news. Indeed, the very notion of debating the topic of Fairuz, to say nothing of expressing disdain for her perspective, conflicts with the prevailing Lebanese consensus. In fact, expressing any antipathy toward Fairuz is typically considered taboo!

During the night of December 5, some quarters in Tripoli (Lebanon's "other" capital city) experienced widespread protests. In short, those protests followed the arrest by the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) of an individual supposedly associated with the Islamist milieu. The armed riots that shook Tripoli were not restricted to street demonstrations or the single attempt made to attack an LAF barracks. Instead, the protests were accompanied by venomous calls for “jihad” against the LAF, which were broadcast via loudspeaker at a number of mosques. The protests soon became newsworthy in Lebanon and ultimately claimed a prominent place in Lebanese current events.

This demonstration of a patently anti-LAF perspective could be seen as the culmination of a cycle of violence that had persisted in Lebanon for months. In fact, events of varying severity that pitted Sunni militants against members of the LAF took place weekly and often on a daily basis. Such confrontations were not restricted to Lebanese Islamists, as they also involved a generally Sunni-oriented platform that united Lebanese, Palestinian and Syrian participants.

Reflective of Lebanon's unique demographics, its army is comprised of personnel that embody the country's confessional mix. Yet while the LAF has shown no clear indications of division at this point, its unity cannot be guaranteed in the future. Moreover, while preservation of the army's relative cohesion is vital, it is equally if not more important that it be perceived as being unbiased in order to retain that objective unity. Sadly, as the December 5 incident (and a host of others) proved, that is not the case. As with other armies in the Arab world, the LAF is steadily increasing its engagement in the “war on terrorism,” which is being waged against Islamists. Thus, since Hezbollah sees itself as being at war against the same enemy as its counterparts in Syria, the mainstream Lebanese Sunni perspective on the LAF becomes easier to understand. Nevertheless, such a comparison necessitates very deliberate consideration. In Lebanon, the prevailing view of the LAF's intelligence branch and General Security apparatus is that both are essentially controlled by Hezbollah. In contrast, the intelligence branch of the Internal Security Forces is seen as little more than the Sunni community's militia, despite the fact that it is "disguised" by the State uniforms worn by its members. Accordingly, we get a sense of the deep crisis being experienced in Lebanon's security sector, which citizens see as the country's last bastion of stability. In other words, although the prevailing trend of the USinfluenced international community is to portray the LAF as a model Lebanese institution that has the ability to preserve stability in Lebanon and provide the template on which other State institutions should be based, reality is markedly different from that panacea. Since portions of Lebanon's population view that institution as shifting between simply being biased and being overtly hostile, the LAF certainly can no longer be considered a suitable model for national cohesion.

The year also saw another, albeit far less honorable source of national cohesion falter within the ranks of the political class. State corruption, which has long been an issue upon which the country’s elites have managed to sustain a “working arrangement” (despite the country's many ills), became the source of new rifts. For instance, Lebanon experienced several hours of extremely heavy rain on December 4. While traffic jams and electricity outages are somewhat routine byproducts of treacherous weather conditions, that particular storm caused severe flooding in two relatively new and important tunnels that connect Beirut to the south. Cars, minibuses and trucks were overwhelmed by the fast-moving water in those tunnels, and army, civil defense and police forces had no choice but to commence emergency rescue operations. While everyone expected heated debates between the officials in charge of those operations, no one anticipated that the assignment of specific responsibilities would extend beyond promises of “severe consequences for those responsible for the calamity.” Yet the aftermath of the storm challenged all expectations. In fact, the Lebanese were treated to unprecedented instances of verbal jousts that involved the minister of public works and transport (Druze) and the minister of finance (Sunni). In those altercations, the two ministers involved (both members of the pro- Hezbollah caretaker government led by Najib Mikati) accused each other of theft or attempted theft of public funds. Those accusations spawned numerous scandals and hints of the same that would involve public figures as well as those considerably less public. But while some aspects of the dispute are interesting to examine, other features are far more thought provoking.

As is the case in many other countries, corruption, especially when it is related to politics, is not unique in Lebanon. Yet it is quickly becoming clear that such malfeasance, which ultimately affects the cohesion of the ruling politicos regardless of their affiliation, is no longer capable of ensuring political "effectiveness." It is equally interesting to note that accusations of corruption are no longer restricted to the list of “usual suspects.” Today, such charges target entities and individuals heretofore shielded from such recriminations by their ability to intimidate others and scandals that involve Hezbollah’s protégés are now within the realm of public gossip. However, the most flagrant demonstration of intolerance to corruption, especially within the Shia milieu, comes via the articles published in a dissenting “Shia-oriented” news website about Randa Berri, the spouse of speaker Nabih Berri. Notably, Berri and his wife have distinguished themselves as pacesetters in the lengthy race of Lebanese corruption.

It is also worthwhile to examine the political platform of Lebanon's Shia community. A renowned rule of war was prescribed more than 1400 years ago by Ali bin Abi Taleb, to whom the Shia attribute themselves. It states, “No one can be attacked at home without ultimately losing their self-esteem.” It is likely that the Syrian people experienced that very feeling when Hezbollah and other foreign fighters began to support the Assad regime. However, that sentiment is not unique to the Syrians. Following the numerous bombings that occurred in Dahiyeh, the repeated shelling of Hermel and other minor but no less forceful incidents, the Lebanese Shia have begun to experience similar feelings. One might even say that the Shia community reacted more harshly to the loss of its self-esteem than did their Syrian counterparts. The self-esteem of Lebanon's Shia community reached a crescendo in the aftermath of key events, such as Israel's withdrawal from south Lebanon in 2000, the socalled “divine victory” in the 2006 War, the forceful dismantling of Hariri-led, Lebanese political Sunnism in May 2008 and Saad Hariri's humiliating overthrow in January 2011. These victories, whether real or imagined, inculcated a distinct sense of arrogance into mainstream Shia public opinion. Today, however, community enthusiasm about Hezbollah’s military involvement in Syria is slowly giving way to a growing sense of fear. Because that apprehension is reflected in the expansion of sectarian solidarity among the Shia, the support that community gives Hezbollah should not be permitted to obfuscate the truth. The same situation is affecting the Sunni community, a situation that has opened the door to Salafist groups (such as an-Nusra and other al-Qaeda-affiliated groups) to advertise themselves as protectors of Lebanon's Sunni community. When we examine the other side of that arrogance "coin" vis-à-vis the growing death toll in Syria, or even more painfully through the fact that involvement in Syria has failed to protect the country (especially its Shia population) from violence at home, we realize that it has brought violence and insecurity closer to Lebanon than ever before. Indeed, Hassan Nasrallah's proud warning to Israel, “If you hit Dahiyeh, we will hit Tel Aviv,” no longer holds any weight. As evidenced by the series of attacks to which that Beirut quarter has been subjected recently, compounded by steady decreases in real estate market prices, it is abundantly clear—especially to residents—that Dahiyeh is no longer an unassailable stronghold.

While 2013 will end with Lebanon surpassing its ominous record for “ministerial crises,” the initial portion of 2014 (and its final few months) will be dominated not only by concerns about security or the steady decay of the country's services, but instead by the matter of electing a successor to outgoing President Michel Suleiman. Once again, the Lebanese must come to terms with the impossible task of meeting the deadline associated with the expiration of the president's mandate.

In order to appreciate the true gravity of this issue (particularly from a Maronite perspective), one must recall that since the 2005 withdrawal of Syrian forces from Lebanon, the role and persona of Lebanon's president is of paramount importance to Lebanon's Christians in general, and particularly to its Maronite community. While Syria’s "yes-man" General Émile Lahoud spent the final years of his mandate virtually quarantined in the Baabda presidential palace, he was eventually accused of politically whitewashing the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri. Moreover, the election of incumbent President Michel Suleiman occurred only through a package deal concluded in Doha following Hezbollah's punitive campaign of May 2008 against its domestic opponents.

Aside from the fact that the last two Lebanese presidents have come from the military (a characteristic that calls into question the ability of the Maronite political elites to identify a truly “eligible” figure), we must understand the significance of several key issues. First, following the assassination of former Prime Minister Hariri and the subsequent withdrawal of Syrian troops, Lebanese Christians (especially its Maronite population) were given the chance to offset the "frustration" associated with the Taif Agreement and the marginalization of its strongest leaders (Samir Geagea was imprisoned in 1994, and Amin Gemayyel and General Michel Aoun were exiled). Next, in the eight years following that perceived turning point, the Maronite community essentially returned to square one—if not a worse situation. Today, that community is being held hostage by the Sunni-Shia conflict. As a result, General Aoun has pledged allegiance to the Syrian-Iranian axis, (represented domestically by Hezbollah) and Lebanese Forces leader Samir Geagea has made a similar pledge to the Sunni axis championed by Saudi Arabia and its domestic friends (i.e., the Hariri "establishment"). But the growing rift within the Maronite community is not confined to the current crowd of political actors. Since Bishop Raii's accession to the office of Patriarch in 2011, his views on the transition of the Arab World (the "Arab Spring"), including Syria, have been so inconsistent and contradictory that they played a large part in not only attenuating the historical moral authority of Bkerki over the flock, but also in aggravating the cracks within the community.

A shared leitmotiv among Lebanon's Christian leaders regarding the matter of the presidency is the need for a “strong” character. Yet the fact that a requirement indeed exists for someone who exudes such strength also insinuates that every previous president was essentially “weak.” Further, it restricts the candidate pool to just four individuals (from oldest to youngest): General Michel Aoun, former president Amin Gemayyel, LF leader Samir Geagea and Marada leader former minister Suleiman Frangiyyeh. Under the current circumstances in Lebanon and with the regional conflict pitting Iran and Saudi Arabia against each other, not one of these so-called "strong leaders" seems especially capable of presiding effectively over the country, particularly as the occupant of an office made largely honorific by the Taif Agreement. For instance, should Geagea win, it would represent a victory for the Saudi-led axis, but should Aoun or Frangiyyeh win, that outcome would translate to victory for the Iranian-led axis. Finally, Gemayyel's election would equate to a compromise situation for the two regional superpowers involved. However, none of these scenarios seem realistic. At this point, therefore, Lebanon's future hangs in the balance. It dangles precariously between an extension of President Suleiman's mandate (which would require an amendment to the Lebanese constitution), “promotion” of the chief of staff to the office of the president (as happened with Generals Lahoud and Suleiman and requires not only a constitutional amendment, but also formal elections) or the election of a “weak” president. Clearly, all three scenarios imply some “entente” between regional and international actors involved with Lebanese politics. A final scenario, one that is neither unrealistic nor worthy of dismissal, is that the country could conceivably reach the May 24, 2014 election deadline without having elected a president. In that case, the country would be plunged again into a presidential void!

All told, the current political impasse is compelling many of the country's leading Christians to intimate that the slight ray of hope that appeared ever so briefly in 2005 has indeed been extinguished. Little wonder, then, that the rhetorical question about whether President Suleiman will be “Lebanon's last Christian president” must be understood as a reflection of the crisis facing the country's Christians—at a time when overall Christian representation in the Middle East is at a historic low.

|

|

|

|

|

Even as 2013 was drawing to its end, there was still time enough to stage another large-scale bombing in Beirut. The December 27 attack killed at least eight more Lebanese, including former finance minister and Hariri establishment strategist Mohammad Chatah. The explosion occurred— coincidentally or otherwise—just a few hundred meters from the site of the huge bombing that killed Rafik Hariri on February 14, 2005 and triggered Lebanon's new dynamics. Likewise, some details of the December 27 bombing are mirror images of those related to Hariri's assassination. For instance, the first claim of responsibility for Hariri's death appeared in an amateurish video submitted allegedly by “Islamists.” Just hours after the December 27 bombing, leaks of dubious veracity ultimately affirmed that the car used in the bombing, stolen years before, had transited the Ain el-Helwe Palestinian camp (home to several Islamist groups) before it was detonated.

The above three pictures of massive destruction could well have been images of the same site. From left to right: the Ruweiss/Dahiyeh bombing (August 15), the Iranian Embassy bombing (November 19) and the Starco/Chatah bombing (December 27).

|

|||

•

|

|

|

A prominent news headline that appeared near the end of 2013 explained that Lebanese singer Fairuz (a Greek Orthodox Christian) likes Hassan Nasrallah and supports Hezbollah. That revelation was made public in an interview published on the Hezbollah-affiliated website al-Ahed. More specifically, it gained credibility because the person being interviewed was her son Ziad Rahbany, a musician and intermittent columnist for the pro-Hezbollah newspaper al-Akhbar. Although Rahbany family representatives—including Fairuz's daughter Rima—tried to weaken the impact of Ziad's disclosure, the damage had already been done. Thus, Fairuz's stature as an invulnerable, pan-Lebanese icon not only became a topic of debate, but also of mockery.

The photoshopped image above, which was widely published on social media sites, features Fairuz in the midst of a typical Hezbollah demonstration wearing a chador and carrying its flag!

|

That statement triggered a wave of comments, both supportive and derogatory. In response, particularly to the negative impressions, Ziad Rahbany appeared the following day on al-Mayadeen TV and stated that any Lebanese who liked neither Fairuz nor Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah was an Israeli sympathizer. In order to understand the magnitude of this disclosure, one must first recognize that among Lebanon's icons, Fairuz epitomizes the notion of good over evil, nurturing mother versus lady of the night; someone who is consistently discerning rather than neglectful. Notably, those involved in this complex chain of actions and reactions were by no means random users of Facebook and Twitter. For instance, Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, historian Fawwaz Traboulsi and even Hassan Nasrallah became involved, which propelled the matter to the forefront of Lebanese news. Indeed, the very notion of debating the topic of Fairuz, to say nothing of expressing disdain for her perspective, conflicts with the prevailing Lebanese consensus. In fact, expressing any antipathy toward Fairuz is typically considered taboo!

•

During the night of December 5, some quarters in Tripoli (Lebanon's "other" capital city) experienced widespread protests. In short, those protests followed the arrest by the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) of an individual supposedly associated with the Islamist milieu. The armed riots that shook Tripoli were not restricted to street demonstrations or the single attempt made to attack an LAF barracks. Instead, the protests were accompanied by venomous calls for “jihad” against the LAF, which were broadcast via loudspeaker at a number of mosques. The protests soon became newsworthy in Lebanon and ultimately claimed a prominent place in Lebanese current events.

This demonstration of a patently anti-LAF perspective could be seen as the culmination of a cycle of violence that had persisted in Lebanon for months. In fact, events of varying severity that pitted Sunni militants against members of the LAF took place weekly and often on a daily basis. Such confrontations were not restricted to Lebanese Islamists, as they also involved a generally Sunni-oriented platform that united Lebanese, Palestinian and Syrian participants.

Reflective of Lebanon's unique demographics, its army is comprised of personnel that embody the country's confessional mix. Yet while the LAF has shown no clear indications of division at this point, its unity cannot be guaranteed in the future. Moreover, while preservation of the army's relative cohesion is vital, it is equally if not more important that it be perceived as being unbiased in order to retain that objective unity. Sadly, as the December 5 incident (and a host of others) proved, that is not the case. As with other armies in the Arab world, the LAF is steadily increasing its engagement in the “war on terrorism,” which is being waged against Islamists. Thus, since Hezbollah sees itself as being at war against the same enemy as its counterparts in Syria, the mainstream Lebanese Sunni perspective on the LAF becomes easier to understand. Nevertheless, such a comparison necessitates very deliberate consideration. In Lebanon, the prevailing view of the LAF's intelligence branch and General Security apparatus is that both are essentially controlled by Hezbollah. In contrast, the intelligence branch of the Internal Security Forces is seen as little more than the Sunni community's militia, despite the fact that it is "disguised" by the State uniforms worn by its members. Accordingly, we get a sense of the deep crisis being experienced in Lebanon's security sector, which citizens see as the country's last bastion of stability. In other words, although the prevailing trend of the USinfluenced international community is to portray the LAF as a model Lebanese institution that has the ability to preserve stability in Lebanon and provide the template on which other State institutions should be based, reality is markedly different from that panacea. Since portions of Lebanon's population view that institution as shifting between simply being biased and being overtly hostile, the LAF certainly can no longer be considered a suitable model for national cohesion.

|

|

|

U.S. Ambassador to Lebanon David Hale presented the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) with a Cessna 208B on November 6, 2013. This was the second such aircraft provided by the US, the first of which it gave to the LAF in 2009. While the aircraft was associated with ongoing US efforts to sustain "strong cooperation between the United States and Lebanon, particularly on the security level," it came just as the LAF increased its engagement in a war being waged against "radical Sunni" elements spread throughout the country. Judging by the numerous incidents that occurred in 2013, the LAF has been challenged by the growing presence of such forces in the country.

To date, the most notable incident of 2013 was the June 23 – 24 clash between the LAF and forces loyal to Salafist Sheikh Ahmad al-Assir in the Saida neighborhood of Abra. The violence ultimately claimed 20 lives, prompted the arrest of more than 60 people and forced Assir to flee to an undisclosed location (most likely the outskirts of the neighboring Palestinian camp of Ain el-Helwe). Likewise, several incidents that pitted the LAF against rogue elements took place in the Bekaa, particularly near the town of Orsal. On May 28 and again on June 6, Lebanese soldiers fired on vehicles that were allegedly transporting armed fighters across the border with Syria to support the war effort. These and other incidents highlight the changing landscape the LAF must confront in Lebanon, to say nothing of its new role as a counterbalance to the growing number of extremist Sunni forces in Syria. On December 19, just days after a mysterious double suicide bombing attack was conducted against two LAF checkpoints in the Saida area, the LAF launched a daylong manhunt near the town and surrounding valleys in search of accomplices to the dead bombers. For the first time ever, Lebanese observers noted that one of the LAF's Cessnas was being used in support of such an operation.

Above, an amateur photograph of the Cessna 208B during the operation mentioned above,

U.S. Ambassador David Hale and a group of LAF officers during the handover ceremony. |

|

•

The year also saw another, albeit far less honorable source of national cohesion falter within the ranks of the political class. State corruption, which has long been an issue upon which the country’s elites have managed to sustain a “working arrangement” (despite the country's many ills), became the source of new rifts. For instance, Lebanon experienced several hours of extremely heavy rain on December 4. While traffic jams and electricity outages are somewhat routine byproducts of treacherous weather conditions, that particular storm caused severe flooding in two relatively new and important tunnels that connect Beirut to the south. Cars, minibuses and trucks were overwhelmed by the fast-moving water in those tunnels, and army, civil defense and police forces had no choice but to commence emergency rescue operations. While everyone expected heated debates between the officials in charge of those operations, no one anticipated that the assignment of specific responsibilities would extend beyond promises of “severe consequences for those responsible for the calamity.” Yet the aftermath of the storm challenged all expectations. In fact, the Lebanese were treated to unprecedented instances of verbal jousts that involved the minister of public works and transport (Druze) and the minister of finance (Sunni). In those altercations, the two ministers involved (both members of the pro- Hezbollah caretaker government led by Najib Mikati) accused each other of theft or attempted theft of public funds. Those accusations spawned numerous scandals and hints of the same that would involve public figures as well as those considerably less public. But while some aspects of the dispute are interesting to examine, other features are far more thought provoking.

|

|

|

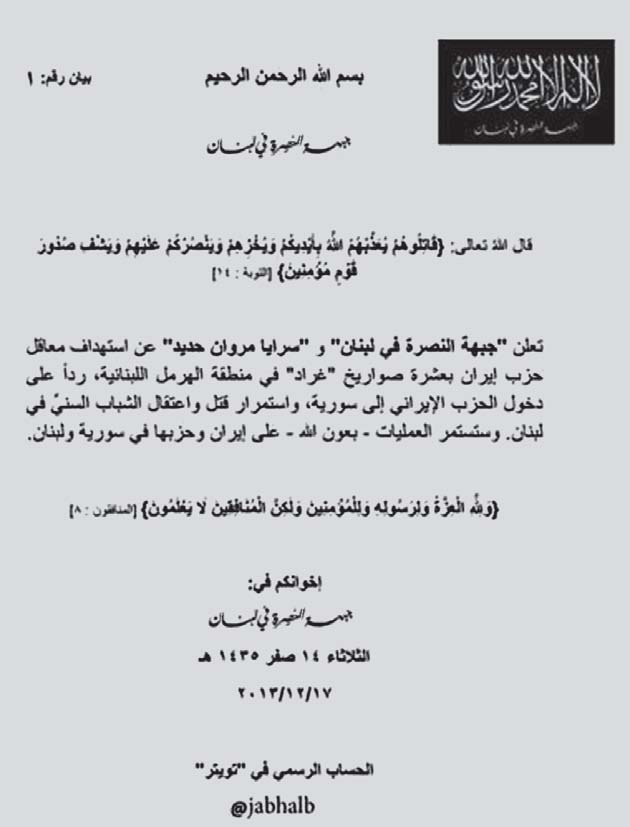

This alleged “first” communiqué of December 17, 2013, which is adorned with several passages from the Koran and Twitter posts, reads: “An-Nusra Front in Lebanon and [the] Marwan Hadid Brigades [a pioneer Syrian Islamist militant killed in 1976] announce the joint targeting with 10 Grad rockets of Iran’s Party strongholds [i.e, Hezbollah] in the Lebanese region of Hermel. This attack [was conducted in] retaliation for Iran's Party involvement in Syria and its [premeditated] killing and [abuse] of Sunni militants in Lebanon. With God’s help, our operations against Iran and its [parties] in Syria and Lebanon will continue.”

|

•

It is also worthwhile to examine the political platform of Lebanon's Shia community. A renowned rule of war was prescribed more than 1400 years ago by Ali bin Abi Taleb, to whom the Shia attribute themselves. It states, “No one can be attacked at home without ultimately losing their self-esteem.” It is likely that the Syrian people experienced that very feeling when Hezbollah and other foreign fighters began to support the Assad regime. However, that sentiment is not unique to the Syrians. Following the numerous bombings that occurred in Dahiyeh, the repeated shelling of Hermel and other minor but no less forceful incidents, the Lebanese Shia have begun to experience similar feelings. One might even say that the Shia community reacted more harshly to the loss of its self-esteem than did their Syrian counterparts. The self-esteem of Lebanon's Shia community reached a crescendo in the aftermath of key events, such as Israel's withdrawal from south Lebanon in 2000, the socalled “divine victory” in the 2006 War, the forceful dismantling of Hariri-led, Lebanese political Sunnism in May 2008 and Saad Hariri's humiliating overthrow in January 2011. These victories, whether real or imagined, inculcated a distinct sense of arrogance into mainstream Shia public opinion. Today, however, community enthusiasm about Hezbollah’s military involvement in Syria is slowly giving way to a growing sense of fear. Because that apprehension is reflected in the expansion of sectarian solidarity among the Shia, the support that community gives Hezbollah should not be permitted to obfuscate the truth. The same situation is affecting the Sunni community, a situation that has opened the door to Salafist groups (such as an-Nusra and other al-Qaeda-affiliated groups) to advertise themselves as protectors of Lebanon's Sunni community. When we examine the other side of that arrogance "coin" vis-à-vis the growing death toll in Syria, or even more painfully through the fact that involvement in Syria has failed to protect the country (especially its Shia population) from violence at home, we realize that it has brought violence and insecurity closer to Lebanon than ever before. Indeed, Hassan Nasrallah's proud warning to Israel, “If you hit Dahiyeh, we will hit Tel Aviv,” no longer holds any weight. As evidenced by the series of attacks to which that Beirut quarter has been subjected recently, compounded by steady decreases in real estate market prices, it is abundantly clear—especially to residents—that Dahiyeh is no longer an unassailable stronghold.

•

|

|

|

Lebanon's Shia community experienced tremendous turmoil during 2013, much of which was associated with Hezbollah's monopolization of that community. Having long since extolled itself as Lebanon's primary military force, Hezbollah simultaneously created the illusion that "its" territory, which stretches from the South to Southern Beirut to the Bekaa, was a virtually impregnable fortress. But that notion was shattered by the series of bombings that shook Beirut's southern suburbs during the summer. On July 9, the first day of the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, a car bomb exploded in the midst of Hezbollah's "security square." That attack was followed by two more, the August 15 explosion in Rouweiss (the heart of Beirut’s southern suburb) that killed some 30 people and the November 19 dual bombing of the Iranian Embassy in Jnah (an upscale quarter of Beirut’s southern suburb), which killed a roughly equal number of people. That violence, which targeted some of Hezbollah's most secure zones, proved that even the organization's so-called "unassailable" areas could be violated by determined attacks. Interestingly, the attacks not only appeared to humanize Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah and his organization, but they also helped contradict previous claims that the group benefitted from divine protection. That change was also noted by mainstream media, particularly in the November 8 broadcast of the comedy show Bas Mat Watan, during which the cast satirized the Hezbollah chief. Supporters of the organization responded by staging two small protests in a Christian area of Beirut. However, the demonstrations were diminutive compared to those of 2006, when massive protests supportive of Nasrallah blocked roads in some Christian quarters—and required Nasrallah's personal intervention to disperse. The ongoing Syrian conflict also contributes to the “humanization” of Nasrallah and his organization. The cartoon above, selected at random from the Internet, reads, “an-Nabk Sweets.” To add perspective, An-Nabk is a city in Qalamoun, Syria, where pitched battles took place between rebels and regime soldiers supported by Hezbollah fighters. In the cartoon, Nasrallah is astounded as he stands near a box of traditional sweets in which the confections have been replaced with coffins draped in Hezbollah flags.

|

In order to appreciate the true gravity of this issue (particularly from a Maronite perspective), one must recall that since the 2005 withdrawal of Syrian forces from Lebanon, the role and persona of Lebanon's president is of paramount importance to Lebanon's Christians in general, and particularly to its Maronite community. While Syria’s "yes-man" General Émile Lahoud spent the final years of his mandate virtually quarantined in the Baabda presidential palace, he was eventually accused of politically whitewashing the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri. Moreover, the election of incumbent President Michel Suleiman occurred only through a package deal concluded in Doha following Hezbollah's punitive campaign of May 2008 against its domestic opponents.

Aside from the fact that the last two Lebanese presidents have come from the military (a characteristic that calls into question the ability of the Maronite political elites to identify a truly “eligible” figure), we must understand the significance of several key issues. First, following the assassination of former Prime Minister Hariri and the subsequent withdrawal of Syrian troops, Lebanese Christians (especially its Maronite population) were given the chance to offset the "frustration" associated with the Taif Agreement and the marginalization of its strongest leaders (Samir Geagea was imprisoned in 1994, and Amin Gemayyel and General Michel Aoun were exiled). Next, in the eight years following that perceived turning point, the Maronite community essentially returned to square one—if not a worse situation. Today, that community is being held hostage by the Sunni-Shia conflict. As a result, General Aoun has pledged allegiance to the Syrian-Iranian axis, (represented domestically by Hezbollah) and Lebanese Forces leader Samir Geagea has made a similar pledge to the Sunni axis championed by Saudi Arabia and its domestic friends (i.e., the Hariri "establishment"). But the growing rift within the Maronite community is not confined to the current crowd of political actors. Since Bishop Raii's accession to the office of Patriarch in 2011, his views on the transition of the Arab World (the "Arab Spring"), including Syria, have been so inconsistent and contradictory that they played a large part in not only attenuating the historical moral authority of Bkerki over the flock, but also in aggravating the cracks within the community.

A shared leitmotiv among Lebanon's Christian leaders regarding the matter of the presidency is the need for a “strong” character. Yet the fact that a requirement indeed exists for someone who exudes such strength also insinuates that every previous president was essentially “weak.” Further, it restricts the candidate pool to just four individuals (from oldest to youngest): General Michel Aoun, former president Amin Gemayyel, LF leader Samir Geagea and Marada leader former minister Suleiman Frangiyyeh. Under the current circumstances in Lebanon and with the regional conflict pitting Iran and Saudi Arabia against each other, not one of these so-called "strong leaders" seems especially capable of presiding effectively over the country, particularly as the occupant of an office made largely honorific by the Taif Agreement. For instance, should Geagea win, it would represent a victory for the Saudi-led axis, but should Aoun or Frangiyyeh win, that outcome would translate to victory for the Iranian-led axis. Finally, Gemayyel's election would equate to a compromise situation for the two regional superpowers involved. However, none of these scenarios seem realistic. At this point, therefore, Lebanon's future hangs in the balance. It dangles precariously between an extension of President Suleiman's mandate (which would require an amendment to the Lebanese constitution), “promotion” of the chief of staff to the office of the president (as happened with Generals Lahoud and Suleiman and requires not only a constitutional amendment, but also formal elections) or the election of a “weak” president. Clearly, all three scenarios imply some “entente” between regional and international actors involved with Lebanese politics. A final scenario, one that is neither unrealistic nor worthy of dismissal, is that the country could conceivably reach the May 24, 2014 election deadline without having elected a president. In that case, the country would be plunged again into a presidential void!

All told, the current political impasse is compelling many of the country's leading Christians to intimate that the slight ray of hope that appeared ever so briefly in 2005 has indeed been extinguished. Little wonder, then, that the rhetorical question about whether President Suleiman will be “Lebanon's last Christian president” must be understood as a reflection of the crisis facing the country's Christians—at a time when overall Christian representation in the Middle East is at a historic low.

•

|

|

|

Throughout 2013, the Christian milieu was largely concerned with the upcoming presidential elections. Much of Lebanese President Michel Suleiman's tenure, due to expire in May 2014, was dedicated to maneuvering among the embattled political parties and trying to appear as objective as possible. But as the level of difficulty continued to increase,it became steadily more challenging for the president to create space to maneuver. Indeed, no single topic was more politically charged than Hezbollah’s announcement of military support for the Syrian regime, which the president condemned outright. Of course, that declaration made Suleiman appear more aligned than ever with the March 14 camp. Beyond the presidential election, the Syrian conflict, an increase in radical,Salafist trends and pervasive "real estate issues" underscored the lingering question about the very presence of Christians in Lebanon in particular and in the Levant in general. Aside from those developments, however, the Lebanese Maronite Church experienced a new and traumatic first during 2013.

The Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith completed its investigation of Lebanese priest Mansour Labaki on October 8 and sentenced him to perform solitary penitence in a Lebanese monastery on charges of child abuse. Not only is the subject of child abuse a quasi-inviolate taboo in Lebanon, but actually holding someone accountable for such actions also breaks yet another cardinal rule. Notably, the Vatican has refused to permit Labaki the opportunity to mount any defense against the charges. The photograph above appears on a website that holds Labaki in a favorable light: www.affairelbk.com

|

On November 22, 2013, Lebanon celebrated the 70th anniversary of its independence. Significantly, that emancipation occurred in the midst of World War II (1943) and was the result of mute competition between France Libre (led by Charles de Gaulle) and Britain. That independence, which certainly deserved a joyful celebration, became a day like any other, to the point that even the military parade went almost unnoticed. In an editorial that marked the day, a journalist renowned for his avowed “Libanism” aptly asked at the opening of his article "Does Lebanon Still Exist?"

While it is true that Lebanon’s founding partisan and nonpartisan myths are indeed fading, no one has the prescience to predict the country's future. Even as 2013 drew to a close, for example, there was still time enough for another largescale bombing in Beirut. Notably, the attack of December 27 killed at least eight more Lebanese, including former finance minister Mohammad Chatah, a stalwart of the March 14 Alliance. Thus, despite the litany of positives the country still offers, the Lebanese must take stock of the words written by French poet Patrice de La Tour du Pin, “Countries that lose their legends are doomed to die from the cold!" Discounting the effects of any more catastrophes, Lebanon is certainly not dead. Nevertheless, it is shivering violently from the cold about which du Pin warned.

While it is true that Lebanon’s founding partisan and nonpartisan myths are indeed fading, no one has the prescience to predict the country's future. Even as 2013 drew to a close, for example, there was still time enough for another largescale bombing in Beirut. Notably, the attack of December 27 killed at least eight more Lebanese, including former finance minister Mohammad Chatah, a stalwart of the March 14 Alliance. Thus, despite the litany of positives the country still offers, the Lebanese must take stock of the words written by French poet Patrice de La Tour du Pin, “Countries that lose their legends are doomed to die from the cold!" Discounting the effects of any more catastrophes, Lebanon is certainly not dead. Nevertheless, it is shivering violently from the cold about which du Pin warned.

Print

Print Share

Share