May 01, 2014

Sunni Minister of Interior Nohad al-Machnouk) was attended by the head of the state security services and the most senior figure in Hezbollah's public intelligence organization (Hajj) Wafic Safa

Officially, the intent of the meeting was to discuss the challenge presented by Tufeil, a Lebanese enclave just inside Syrian territory.

Despite reports probably leaked by Machnouk's own entourage that he addressed Safa as “a de facto force in Syria,” the photograph taken of the meeting told a markedly different story. In the tastefully appointed conference room, the Hezbollah representative was essentially granted peer status to the other state representatives in attendance. As picture is worth a thousand words, the treatment accorded Mr. Safa prompted reprobation from journalists and individuals affiliated with March 14.

The apparently pro forma meeting, accompanied by the patently incriminating photograph, are in fact just the tip of the iceberg. After all, that escarpment seems to obscure the myriad "facts" that have been trumpeted about political life in Lebanon since the beginning of the year. Amidst Lebanon's unpredictable security situation in early in 2014, signs of rapprochement began to appear between the opposing camps (primarily Hezbollah and the Hariri establishment).

Those signs solidified to a degree when a new government, presided over by Tammam Salam, a weak, Beirut-based Sunni figure, was finally formed, an outcome tantamount to an internationally blessed regional agreement on the preservation of Lebanon’s so-called stability. Ultimately, however, those actions reduced Lebanon’s priority on the list of regional concerns. Importantly but unfortunately, more effort was invested in maintaining Lebanon's appearance as a country with functioning institutions, with particular attention given to its military and security services.

That "maintenance" effort centered on providing Lebanon the funding and “moral support” it desperately needs to “host” more than a million Syrian refugees in addition to the hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees who already call Lebanon home. To date, however, no genuine effort has been made to stop the steady flow of refugees into Lebanon by attempting to foment a solution to the ongoing Syrian tragedy. Similarly, no worthwhile effort has been made to disassociate Lebanon from the crisis in Syria by pressuring Iran to terminate Hezbollah’s involvement in that country's civil war.

The first public signs of the rapprochement between Hezbollah and the Hariri establishment appeared last January (2014) when Mohammad Raad, who heads Hezbollah’s parliamentary bloc, and Saad Hariri offered conciliatory statements that opened the door to the formation of a new government. However, cryptic signs of that development were noted earlier because of ongoing engagement between senior political figures including Fouad Siniora (former prime minister and head of the Future parliamentary bloc), Nabih Berri (head of the Amal Movement and parliament speaker) and Walid Jumblatt (leader of the Druze). But less public figures were also involved in that process, such as businessmen (of all stripes) who share an interest in sustaining their businesses.

Yet, while the Lebanese public was following the debate over retaining or excluding the keyword "Resistance" in the Ministerial statement, relations between the Hariri establishment and Hezbollah were warming. News of that "progress" vacillated between remaining discreet and being released in a blatantly public manner, such as the visit made several days before the formation of the new government to Brigadier General Samir Shehade (head of the ISF office in Saida) by the same Wafic Safa mentioned above. That particularly public visit took on substantial meaning in view of General Shehade's curriculum vitae. Specifically, while Shehade was serving at the ISF Intelligence Office (a partner to the international investigation into the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri) in September 2006, he was the target of an assassination attempt that killed four of his bodyguards. According to some sources, the investigation into that assassination attempt disclosed that the bomb was similar to those used previously against anti-Hezbollah ministers Marwan Hamade and Elias al-Murr. After the attempt on his life, General Shehade relocated to Canada for several years before eventually returning to Lebanon in the course of 2013, apparently part of a deal brokered after the assassination of General Wissam al-Hassan. Although General Shehade officially leads the ISF head office in Saida, he is reputedly the real boss of the ISF intelligence department.

al-Assir (who remains vocal despite having been ousted in a military operation conducted in June 2013). From Hezbollah’s viewpoint, Saida is a critical gateway to and from south Lebanon that must remain open. Of note, the Saida region also includes Ain el-Helwe, the largest of Lebanon's Palestinian refugee camps, which is home to an increasing number of radical Islamists as well as smaller Palestinian camps and pockets. The area also serves as a sounding board for the heated debates over internal Palestinian affairs between President Mahmood Abbas and his opponents. Further, it is a consistent source of headache for everyone, including nations that contribute soldiers to UNIFIL, since several attacks against that international peacekeeping body originated in Ain el- Helwe.

Indeed, the Hezbollah-Hariri politicalcum- security entente seems to extend well beyond Lebanese issues to encompass Palestinian considerations as well. A particularly bloody illustration of that extension took place on April 7 in Mieh-Mieh, a small Palestinian camp located four kilometers east of Saida. On that date, the Palestinian group “Ansar Allah” (The Allies of God), known to be on Hezbollah's payroll, decimated another Palestinian group. The attack, which killed 9 and injured 10 more, was a premeditated attempt to exterminate the Palestinian group “Kataeb al-Awda” (The Legions of Return). The latter group is headed by Ahmad Rashid, a vocal supporter of the Syrian uprising, close to the former leader of Fatah in Gaza Mohammad Dahlan and bête noire of Hamas and Mahmoud Abbas.

As described in some reports (specifically an-Nahar), various Palestinian sources stated that the attack against Kataeb al-Awda was conducted after Ahmad Rashid “opened the path of membership in his Legions to people from Fatah as well as Syrian refugees who he [had begun] training and arming and who represented a [genuine] danger not only to the camps [at large], but also to Syrian security.” Other Palestinian sources quoted by Janoubia stated that the attack was "similar to the [one that] dissolved Sheikh Ahmad al-Assir's group in Saida [last June]. [As a result,] Hezbollah now enjoys full control of the Saida region and the camps [located there]."

In apparent confirmation of the fact that this brutal strike was green-lighted by a higher authority, and despite its alarmingly high death toll, neither the Lebanese nor the Palestinian authorities have commenced any meaningful investigation into the event! Interestingly, some media reports indicated that a member of Assir's group was caught in Mieh Mieh following that attack.

While the strike derives clearly from the atmosphere of entente, it also reflects intra-Palestinian developments occurring within camps in Lebanon, the West Bank and Gaza to control or at least contain events in Ain el-Helwe and its smaller cousins in south Lebanon. That area will remain a common interest as long as the détente between Hezbollah and the Hariri establishment perseveres.

In view of the foregoing, it is clear that the “security entente” illustrated by Safa's visit to Shehade, and the picture of him sitting amiably among the leaders of Lebanon's security apparatuses, is but one element in a comprehensive policy based on the general orientation of each side. For instance, if we accept the assertion that the Hariri establishment/ Future Movement represents (or purports to represent) “moderate Sunni Islam in Lebanon,” and we acknowledge that Hezbollah rages against radical Islamists, then radical Islamists are an enemy common to both organizations. As this particularly comprehensive policy is actively encouraged by the patrons of the Hariri establishment/Future Movement and Hezbollah (Saudi Arabia and Iran, respectively), the decreased support being shown by the Future Movement/Hariri establishment for the Syrian uprising and its relative silence on Hezbollah's involvement there becomes easier to understand—despite the Future Movement/Hariri establishment having originally championed support for the Syrian opposition.

Moving away from the south, it is evident that something similar happened in the north. While no convincing explanation has yet been given for the 20th round of violence in Tripoli (among the most violent and lethal examples to date), few Lebanese doubted that the government's security plan for Tripoli (which was adopted by Tamam Salam's “national interest” government) would fail. Contrary to previous approaches, assurances of the effectiveness of the most recent plan were based on the certainty that the interests of Hezbollah and the Future Movement would indeed converge again—with the blessing of their regional and international patrons.

Nevertheless, a somewhat droll twist in this "certain" security plan occurred when the names of everyone being sought by the authorities were leaked 48 hours before the plan commenced, which enabled most of them to escape.

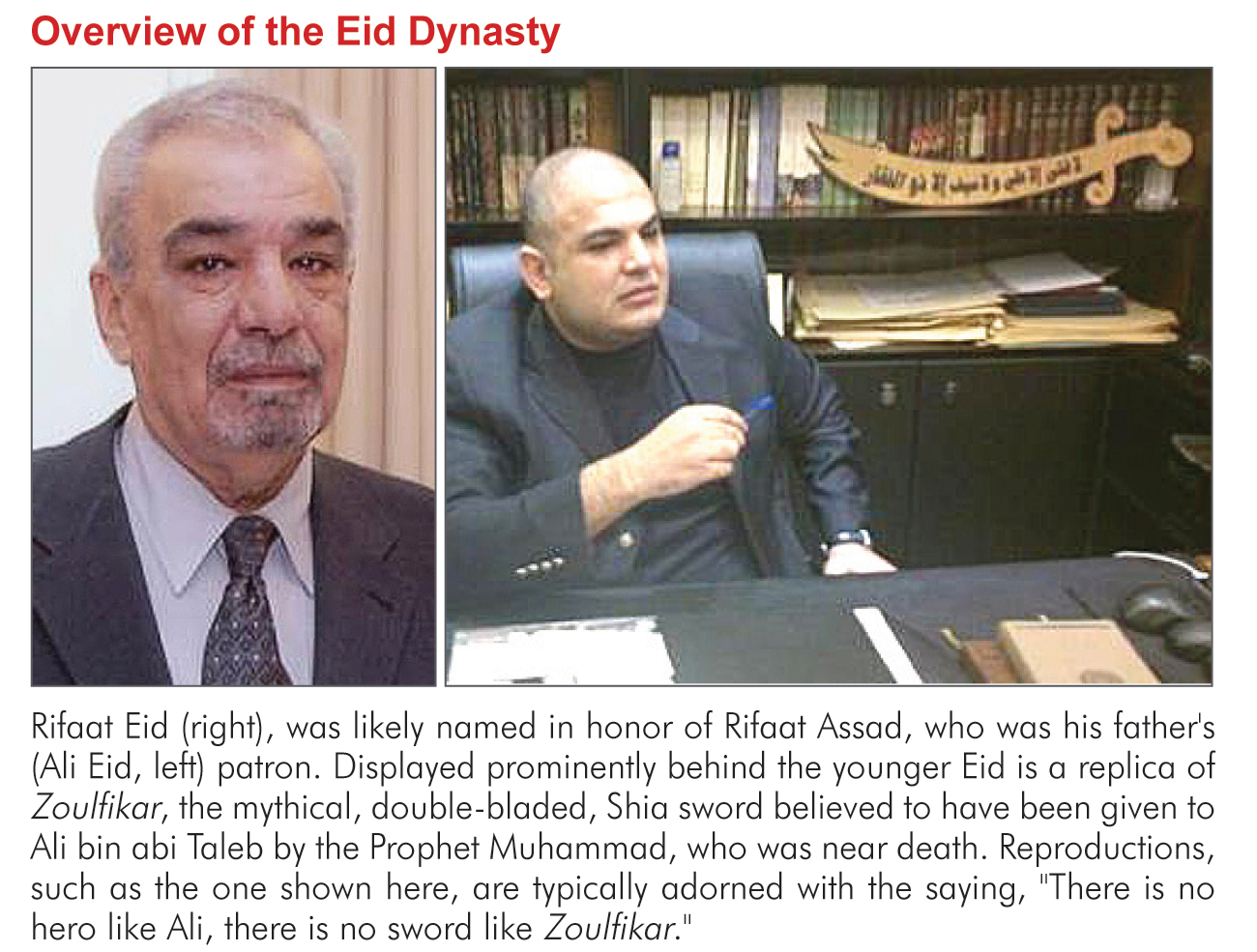

Equally surprising, however, was that Hezbollah abruptly dropped its association with the Eid clan, al-Assad’s longstanding Alawi pawns and protégés in Tripoli. Today, Ali (father) and Rifaat Eid (son) are under arrest warrants, and their residences were raided by the Lebanese army. From a cultural perspective, both suffered a debilitating humiliation and were forced to flee as submissively as the Sunni “front leaders” (kadat al-Mahawer) in Tripoli against whom they were pretending to defend their “people.” Clearly, Hezbollah's actions relative to the Eid family and the comparatively low-key approach it took when it equated the father-son duo to what its media outlets always described as trivial gang leaders would have been impossible had it not consulted previously with the highest Syrian authorities. Similarly, the Assad regime's acquiescence to Hezbollah's actions would not have occurred absent a logical raison d'état. Obviously, the only entity able to impose its will on Hezbollah and the Assad regime is Iran, and it was the Iranian raison d’état that prompted Hezbollah to both accept the formation of a national interest government and downgrade the Eid family to a band of outlaws—among other formal “concessions.” The supreme leverage exacted by Iran thus becomes a key to understanding Lebanon’s so-called stability and the patently miraculous functioning of its governmental institutions.

Assuming that abandoning the Eid dynasty and consequently Jabal Mohsen represents a lofty price that can only be paid via a comprehensive raison d’état, it becomes clear that the underlying rationale was twofold in nature. First, the Syrian army and its allies (including Lebanese and Iraqi militias and possibly other nationalities as well) would assume control of the Qalamoun region near the Lebanese border. Second, the Hariri establishment and its Saudi patrons would agree to abandon Orsal, which for years was praised as a Sunni bastion in the northern Bekaa.

Finally, in a very atypical move, Lebanon's civil and military judiciaries recently released three individuals. They included two Shia clerics, Sayyid Mohammad Ali and Sheikh Hassan Mchaymech. Al-Husseini was arrested in Lebanon in May 2011 while Mchaymech was originally taken into custody on July 7, 2010 along the Lebanese-Syrian border by Syrian security but reappeared in Beirut in October 2011 in the custody of the ISF. Both men were accused of collaborating with Israel, and both were sentenced by the first-degree Lebanese military court. The third individual, Salah Ezeddine (dubbed by Lebanese and foreign press outlets as “Hezbollah’s and Lebanon’s Madoff” due to the financial magnitude of the affairs in which he was involved) was arrested in September 2009. The release of these three individuals indeed raises a number of questions. As noted in an article published April 25, 2014, this unique development has prompted questions and suspicion. But aside from the likelihood that the release is a component of a larger deal, two inherent features are worth being mentioned. First, this surprise development proves yet again that decisions made by the Lebanese judiciary are always highly politicized. Second, this attempt to close yet another file as part of a political deal is simply the latest interpretation of the enduring Lebanese propensity toward closing, rather than completing files, a uniquely Lebanese "habit" that influenced the way Lebanon’s war was ended.

Nevertheless, the Lebanese people and the global community should both be aware that this brand of stability is a very short-term bet that comes at an extraordinarily high price. Perhaps the best description of the cost involved can be summed up by the words of Itamar Rabinovich, a renowned connoisseur of Lebanon:

Sunni Minister of Interior Nohad al-Machnouk) was attended by the head of the state security services and the most senior figure in Hezbollah's public intelligence organization (Hajj) Wafic Safa

Officially, the intent of the meeting was to discuss the challenge presented by Tufeil, a Lebanese enclave just inside Syrian territory.

Despite reports probably leaked by Machnouk's own entourage that he addressed Safa as “a de facto force in Syria,” the photograph taken of the meeting told a markedly different story. In the tastefully appointed conference room, the Hezbollah representative was essentially granted peer status to the other state representatives in attendance. As picture is worth a thousand words, the treatment accorded Mr. Safa prompted reprobation from journalists and individuals affiliated with March 14.

The apparently pro forma meeting, accompanied by the patently incriminating photograph, are in fact just the tip of the iceberg. After all, that escarpment seems to obscure the myriad "facts" that have been trumpeted about political life in Lebanon since the beginning of the year. Amidst Lebanon's unpredictable security situation in early in 2014, signs of rapprochement began to appear between the opposing camps (primarily Hezbollah and the Hariri establishment).

Those signs solidified to a degree when a new government, presided over by Tammam Salam, a weak, Beirut-based Sunni figure, was finally formed, an outcome tantamount to an internationally blessed regional agreement on the preservation of Lebanon’s so-called stability. Ultimately, however, those actions reduced Lebanon’s priority on the list of regional concerns. Importantly but unfortunately, more effort was invested in maintaining Lebanon's appearance as a country with functioning institutions, with particular attention given to its military and security services.

That "maintenance" effort centered on providing Lebanon the funding and “moral support” it desperately needs to “host” more than a million Syrian refugees in addition to the hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees who already call Lebanon home. To date, however, no genuine effort has been made to stop the steady flow of refugees into Lebanon by attempting to foment a solution to the ongoing Syrian tragedy. Similarly, no worthwhile effort has been made to disassociate Lebanon from the crisis in Syria by pressuring Iran to terminate Hezbollah’s involvement in that country's civil war.

The first public signs of the rapprochement between Hezbollah and the Hariri establishment appeared last January (2014) when Mohammad Raad, who heads Hezbollah’s parliamentary bloc, and Saad Hariri offered conciliatory statements that opened the door to the formation of a new government. However, cryptic signs of that development were noted earlier because of ongoing engagement between senior political figures including Fouad Siniora (former prime minister and head of the Future parliamentary bloc), Nabih Berri (head of the Amal Movement and parliament speaker) and Walid Jumblatt (leader of the Druze). But less public figures were also involved in that process, such as businessmen (of all stripes) who share an interest in sustaining their businesses.

Yet, while the Lebanese public was following the debate over retaining or excluding the keyword "Resistance" in the Ministerial statement, relations between the Hariri establishment and Hezbollah were warming. News of that "progress" vacillated between remaining discreet and being released in a blatantly public manner, such as the visit made several days before the formation of the new government to Brigadier General Samir Shehade (head of the ISF office in Saida) by the same Wafic Safa mentioned above. That particularly public visit took on substantial meaning in view of General Shehade's curriculum vitae. Specifically, while Shehade was serving at the ISF Intelligence Office (a partner to the international investigation into the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri) in September 2006, he was the target of an assassination attempt that killed four of his bodyguards. According to some sources, the investigation into that assassination attempt disclosed that the bomb was similar to those used previously against anti-Hezbollah ministers Marwan Hamade and Elias al-Murr. After the attempt on his life, General Shehade relocated to Canada for several years before eventually returning to Lebanon in the course of 2013, apparently part of a deal brokered after the assassination of General Wissam al-Hassan. Although General Shehade officially leads the ISF head office in Saida, he is reputedly the real boss of the ISF intelligence department.

al-Assir (who remains vocal despite having been ousted in a military operation conducted in June 2013). From Hezbollah’s viewpoint, Saida is a critical gateway to and from south Lebanon that must remain open. Of note, the Saida region also includes Ain el-Helwe, the largest of Lebanon's Palestinian refugee camps, which is home to an increasing number of radical Islamists as well as smaller Palestinian camps and pockets. The area also serves as a sounding board for the heated debates over internal Palestinian affairs between President Mahmood Abbas and his opponents. Further, it is a consistent source of headache for everyone, including nations that contribute soldiers to UNIFIL, since several attacks against that international peacekeeping body originated in Ain el- Helwe.

Indeed, the Hezbollah-Hariri politicalcum- security entente seems to extend well beyond Lebanese issues to encompass Palestinian considerations as well. A particularly bloody illustration of that extension took place on April 7 in Mieh-Mieh, a small Palestinian camp located four kilometers east of Saida. On that date, the Palestinian group “Ansar Allah” (The Allies of God), known to be on Hezbollah's payroll, decimated another Palestinian group. The attack, which killed 9 and injured 10 more, was a premeditated attempt to exterminate the Palestinian group “Kataeb al-Awda” (The Legions of Return). The latter group is headed by Ahmad Rashid, a vocal supporter of the Syrian uprising, close to the former leader of Fatah in Gaza Mohammad Dahlan and bête noire of Hamas and Mahmoud Abbas.

As described in some reports (specifically an-Nahar), various Palestinian sources stated that the attack against Kataeb al-Awda was conducted after Ahmad Rashid “opened the path of membership in his Legions to people from Fatah as well as Syrian refugees who he [had begun] training and arming and who represented a [genuine] danger not only to the camps [at large], but also to Syrian security.” Other Palestinian sources quoted by Janoubia stated that the attack was "similar to the [one that] dissolved Sheikh Ahmad al-Assir's group in Saida [last June]. [As a result,] Hezbollah now enjoys full control of the Saida region and the camps [located there]."

In apparent confirmation of the fact that this brutal strike was green-lighted by a higher authority, and despite its alarmingly high death toll, neither the Lebanese nor the Palestinian authorities have commenced any meaningful investigation into the event! Interestingly, some media reports indicated that a member of Assir's group was caught in Mieh Mieh following that attack.

While the strike derives clearly from the atmosphere of entente, it also reflects intra-Palestinian developments occurring within camps in Lebanon, the West Bank and Gaza to control or at least contain events in Ain el-Helwe and its smaller cousins in south Lebanon. That area will remain a common interest as long as the détente between Hezbollah and the Hariri establishment perseveres.

In view of the foregoing, it is clear that the “security entente” illustrated by Safa's visit to Shehade, and the picture of him sitting amiably among the leaders of Lebanon's security apparatuses, is but one element in a comprehensive policy based on the general orientation of each side. For instance, if we accept the assertion that the Hariri establishment/ Future Movement represents (or purports to represent) “moderate Sunni Islam in Lebanon,” and we acknowledge that Hezbollah rages against radical Islamists, then radical Islamists are an enemy common to both organizations. As this particularly comprehensive policy is actively encouraged by the patrons of the Hariri establishment/Future Movement and Hezbollah (Saudi Arabia and Iran, respectively), the decreased support being shown by the Future Movement/Hariri establishment for the Syrian uprising and its relative silence on Hezbollah's involvement there becomes easier to understand—despite the Future Movement/Hariri establishment having originally championed support for the Syrian opposition.

Moving away from the south, it is evident that something similar happened in the north. While no convincing explanation has yet been given for the 20th round of violence in Tripoli (among the most violent and lethal examples to date), few Lebanese doubted that the government's security plan for Tripoli (which was adopted by Tamam Salam's “national interest” government) would fail. Contrary to previous approaches, assurances of the effectiveness of the most recent plan were based on the certainty that the interests of Hezbollah and the Future Movement would indeed converge again—with the blessing of their regional and international patrons.

|

Nevertheless, a somewhat droll twist in this "certain" security plan occurred when the names of everyone being sought by the authorities were leaked 48 hours before the plan commenced, which enabled most of them to escape.

Equally surprising, however, was that Hezbollah abruptly dropped its association with the Eid clan, al-Assad’s longstanding Alawi pawns and protégés in Tripoli. Today, Ali (father) and Rifaat Eid (son) are under arrest warrants, and their residences were raided by the Lebanese army. From a cultural perspective, both suffered a debilitating humiliation and were forced to flee as submissively as the Sunni “front leaders” (kadat al-Mahawer) in Tripoli against whom they were pretending to defend their “people.” Clearly, Hezbollah's actions relative to the Eid family and the comparatively low-key approach it took when it equated the father-son duo to what its media outlets always described as trivial gang leaders would have been impossible had it not consulted previously with the highest Syrian authorities. Similarly, the Assad regime's acquiescence to Hezbollah's actions would not have occurred absent a logical raison d'état. Obviously, the only entity able to impose its will on Hezbollah and the Assad regime is Iran, and it was the Iranian raison d’état that prompted Hezbollah to both accept the formation of a national interest government and downgrade the Eid family to a band of outlaws—among other formal “concessions.” The supreme leverage exacted by Iran thus becomes a key to understanding Lebanon’s so-called stability and the patently miraculous functioning of its governmental institutions.

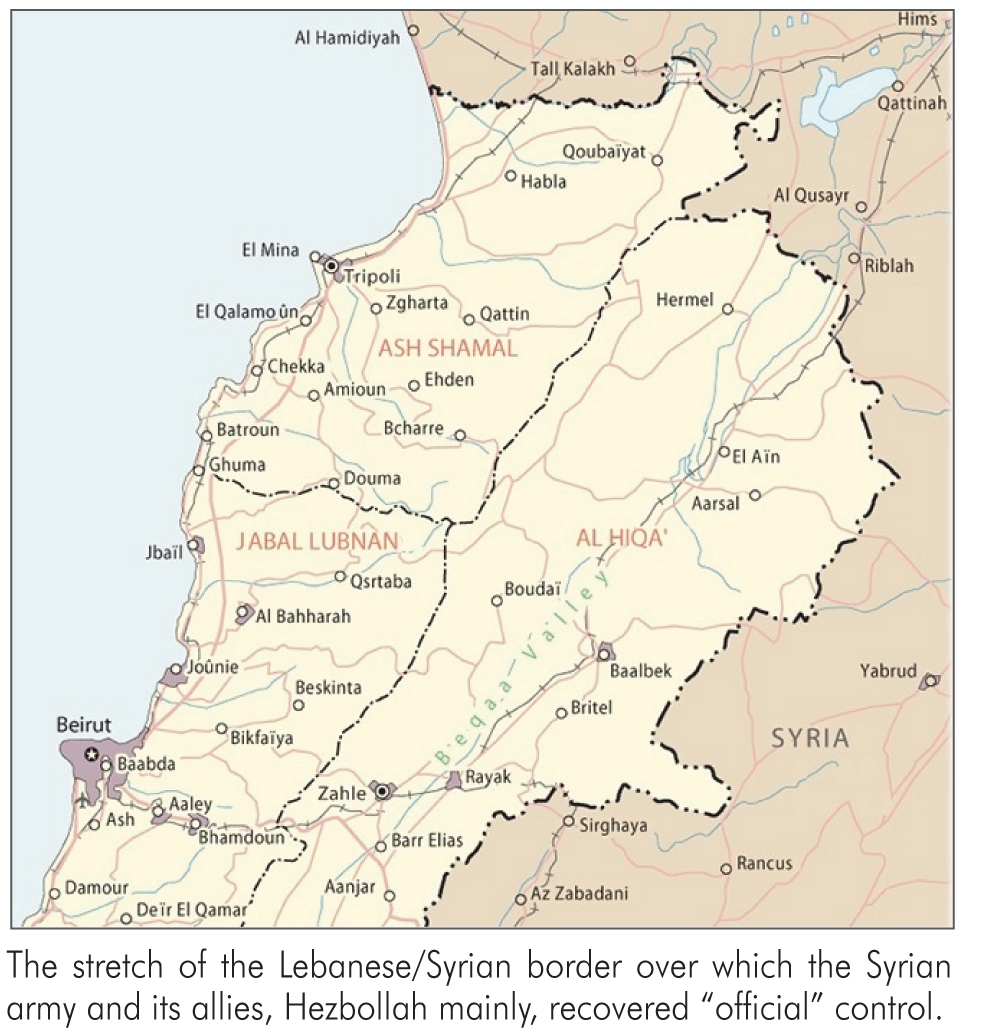

Assuming that abandoning the Eid dynasty and consequently Jabal Mohsen represents a lofty price that can only be paid via a comprehensive raison d’état, it becomes clear that the underlying rationale was twofold in nature. First, the Syrian army and its allies (including Lebanese and Iraqi militias and possibly other nationalities as well) would assume control of the Qalamoun region near the Lebanese border. Second, the Hariri establishment and its Saudi patrons would agree to abandon Orsal, which for years was praised as a Sunni bastion in the northern Bekaa.

Finally, in a very atypical move, Lebanon's civil and military judiciaries recently released three individuals. They included two Shia clerics, Sayyid Mohammad Ali and Sheikh Hassan Mchaymech. Al-Husseini was arrested in Lebanon in May 2011 while Mchaymech was originally taken into custody on July 7, 2010 along the Lebanese-Syrian border by Syrian security but reappeared in Beirut in October 2011 in the custody of the ISF. Both men were accused of collaborating with Israel, and both were sentenced by the first-degree Lebanese military court. The third individual, Salah Ezeddine (dubbed by Lebanese and foreign press outlets as “Hezbollah’s and Lebanon’s Madoff” due to the financial magnitude of the affairs in which he was involved) was arrested in September 2009. The release of these three individuals indeed raises a number of questions. As noted in an article published April 25, 2014, this unique development has prompted questions and suspicion. But aside from the likelihood that the release is a component of a larger deal, two inherent features are worth being mentioned. First, this surprise development proves yet again that decisions made by the Lebanese judiciary are always highly politicized. Second, this attempt to close yet another file as part of a political deal is simply the latest interpretation of the enduring Lebanese propensity toward closing, rather than completing files, a uniquely Lebanese "habit" that influenced the way Lebanon’s war was ended.

Nevertheless, the Lebanese people and the global community should both be aware that this brand of stability is a very short-term bet that comes at an extraordinarily high price. Perhaps the best description of the cost involved can be summed up by the words of Itamar Rabinovich, a renowned connoisseur of Lebanon:

Hizballah is more powerful than the Lebanese state and does not accept its authority. It participates in the governmental coalition and exercises its influence over the Lebanese army. At this point, Hizballah and its Iranian patrons prefer to keep the shell of the Lebanese state as long as they enjoy full freedom to pursue their policies and as long as the Lebanese government does not take any action that is not acceptable to them.

Print

Print Share

Share