August 13, 2014

armed groups” that controlled Arsal for several days before they withdrew. And when they did withdraw in accordance with an “agreement” brokered by the nebulous Sunni-Salafi “Muslim Clerical Association,” those forces took with them their military hardware, their injured and the dozens of Lebanese soldiers and policemen.One of the most recognizable outcomes of the "Arsal debacle" is that it prompted an immediate response by the Saudi establishment—which came in the form of an offer of a billion dollars in aid to Lebanon’s state security forces. Interestingly, this latest Saudi contribution was not made via the conventional state-to-state communication conduit but through former Prime Minister Saad Hariri. Speaking from the stately Jeddah residence he inherited from his father Rafik, the younger Hariri announced on August 6 that King Abdullah “informed [him] of his generous decision to provide the Lebanese army...with $1 billion to strengthen its capabilities to preserve Lebanon’s security.”

Anecdotally, in response to a related question, Saad Hariri sent an indulgent message to Hezbollah. In it, he tacitly validated Hezbollah's statement that it had not engaged in joint military operations in Arsal with the LAF but also characterized Hezbollah’s involvement in the Syrian conflict as "criminal." Just two days after Hariri made the statement (which boosted the leverage of the Hariri dynasty), his private jet landed in Lebanon at Beirut-Rafic Hariri International Airport. Following an immediate stop at his father's tomb, the younger Hariri headed to the Grand Serail to meet with incumbent Prime Minister Tamam Salam.

It is important to note that Saad Hariri's return ended his more than three years of absence from Lebanon due, formally, to issues of security. In review, at the very moment Saad Hariri began his meeting with U.S. President Barack Obama on January 11, 2011, ten members of his cabinet (who were affiliated directly or indirectly with Hezbollah) abruptly announced their resignation. The action caused the government to collapse and stripped Hariri of his responsibilities as prime minister. Since that exceedingly public political humiliation (which also ended Saudi-Syrian-Iranian entente), Saad Hariri self-exiled himself.

In view of the perspective outlined above, it seems logical to opine that despite the general danger in Lebanon and specific threats against him, Saad Hariri's return to Beirut is as significant to the country as was his choice for self-exile. While away, Hariri flitted between Riyadh and Paris, and even made time for a skiing trip to the Alps almost a year after losing office—a jaunt that cost him a broken leg. Adding insult to injury, Sheikh Ahmad al-Assir (at the time a favorite guest of the Lebanese media and talk shows but whose "stardom" has since been outlawed) observed that “…he’s [Hariri] even a bad skier.”

The reference to Sheikh Ahmad al-Assir, who challenged the Hariri dynasty in its hometown of Saida (south of Beirut), is by no means irrelevant to Hariri’s return to Lebanon with a $1 billion letter of credit from King Abdullah to fight terrorism. Some sources have also asserted that Hariri received a few hundred million dollars in “pocket money” to resurrect the once formidable influence the Future Movement wielded within the Sunni community and welcome back to the fold all those who no longer look to Riyadh as the only Sunni address in Lebanon and in the region.

|

|

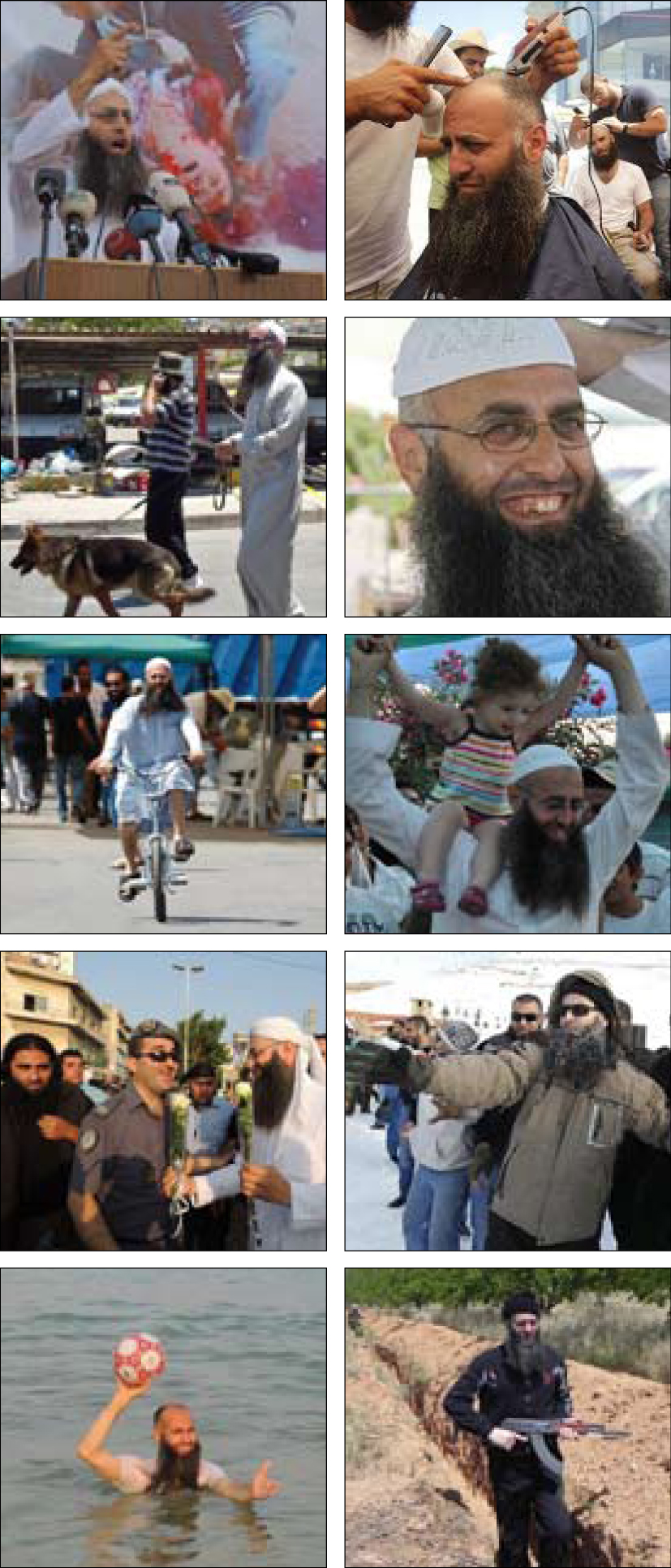

Although Sheikh Ahmad al-Assir is not always taken seriously by the Lebanese establishment because of his casual/populist behaviors (some of which are captured in the pictures above collected randomly on the Internet), he has become a lightning rod. Born in 1968 ostensibly to a mixed Sunni (father)/Shia (mother) family, al-Assir quickly began to ascend the public ladder on a national scale in 2011. His popularity was confirmed in June 2012 when he called for a rally in Martyrs' Square to commemorate and denounce Hezbollah's punitive campaign of May 2008 and demonstrate solidarity with the Syrian uprising. Importantly, al-Assir seemed to fulfill a real expectation, if not a genuine need for self-confirmation within the Sunni milieu. The Hariri establishment dealt lightly with the al-Assir phenomenon (and other Sunni movements toward extremism) as evidenced by its failure to manipulate them in an effort to deter Hezbollah.

Today, Sheikh Ahmad al-Assir is being judged in absentia by Lebanon's military court, a development which proves that the “turbaned clown,” a derisive moniker used by some Lebanese, was certainly not clownish. For instance, the June 2013 assault on al-Assir's Abra stronghold near Saida killed numerous Lebanese Armed Forces soldiers. The families of al-Assir's followers apprehended during the assault continue to organize impromptu sit-ins to demand that those arrested be judged quickly. Finally, a report by Wafic Hawwari (a connoisseur of Saida issues and moods) published recently to coincide with the one-year anniversary of the Abra assault that crushed the Sheikh's stardom and made him an outlaw, asserts that “one year after [that battle,] Saida is more sympathetic to al-Assir [than before].” But while Sheikh al-Assir's rise can be understood from a political perspective, the generous funding he received to sustain activities that seemed patently theatrical remains shrouded in mystery. By extension, the assertion that al-Assir enjoyed Qatari funding from the beginning of his stardom until today is one that not even the Hariri establishment would dare endorse. Since an accusation of that kind would be tantamount to meddling in inter-Gulf issues, even the thought of acknowledging such conditions is taboo! |

The threat Lebanon is facing today makes the country part of the region's greater theater of operations, and that reality is unconditional. At the same time, it becomes a point of convergence for the Hariri establishment and Hezbollah, clients of Saudi Arabia and Iran, respectively. Moreover, while the longstanding identity and leadership crisis that affects the Lebanese Sunni community is a key factor in the danger creeping in on Lebanon, one question must be asked. Is Saudi Arabia's policy of “disbursement” that consistently pumps cash into Lebanon's security organizations and/or the pipelines of its Lebanese clients sufficient to contain the identity crisis being expressed by the Lebanese Sunni community and convince it not to heed the siren call of extremism?

Until proof is given to the contrary, one may remain justifiably unconvinced that Saad Hariri's seemingly messianic return home with a billion Saudi dollars earmarked for “fighting terrorism” will indeed be able to check the growing identity crisis among the Lebanese Sunni and lead that community back into the fold of “moderation.” Two rationales, at least, argue in favor of skepticism.

• To date, the effectiveness of the Saudi policy of “disbursement,” which that country uses to promote its own agenda, has proved to be limited not only in Saudi Arabia, but also in other parts of the world—including Lebanon. The reasons behind its limited effect are very simple: without a well-defined vision coupled with an ill-informed Weltanschauung, cash alone, regardless of the sums involved, is eventually invested “in the cause” (the best-case scenario) or frittered away by corruption.

In today's struggle for hearts, minds and influence, Saudi Arabia has done very little since 9/11 to clarify and exemplify its concepts of “moderation” and “moderate Islam.” Further, the money Saudi Arabia is now ready to spend cannot purchase for its regional allies the type of “conceptual toolbox” being carried by its opponents unless it imposes on itself a revision to the "style" of Islam it observes in order to ensure the stability of the Saudi regime.

In reality, Saudi Arabia appears unable to impart that revision to move forward at home and engage in a genuine reform process through which all underrepresented Saudis—not just the Shia—might benefit. Those changes notwithstanding, Saudi Arabia has very little to offer regionally regardless of the amount of money it spends. Of course, the same can be said of other regional "players," such as Qatar, which also has billions to "invest" as it sees fit.

Still, absent a clear vision and a discrete strategy, the dollars those countries are disbursing are doomed to ignominious and unaccountable loss or consignment to "worthwhile commissions."

• Before the Future Movement/Hariri establishment can even attempt to redirect the black sheep of the Sunni community back into the fold of “moderation,” that collective must first commit to a painful reform and renovation of its structure that will help it look more like a family enterprise.

The Movement must also review and address its past performance at the financial high and low tides. It must avail itself of self-criticism by asking a series of pivotal questions. Chief among those, why, despite all of the support the collective has received, has the “value” of Rafik Hariri’s blood and legacy—regardless of what we may think of it—tumbled so dramatically on the political/ideological “market?” By extension, why is it that young Lebanese Sunni prefer to model themselves as “shouhada” for whatever the cause—in imitation of the "heroism card" being played by Hezbollah—rather than become the lovers of life cherished so dearly by March 14? The ability of the Future Movement/Hariri establishment to undergo such a renovation is not only instrumental to the success of its Saudi-backed counter-attack plan, but it will also prove decisive in securing its own future!

On August 24, 2008, days after Lebanese leaders had reached the Doha Agreement (prompted by the mini-war of May 2008 during which Hezbollah thrashed the Future Movement militarily), al-Hayat editorialist Daoud ash-Shiryan published a relentless indictment of the Hariri dynasty/Future Movement titled “The Future of the Future.” , The final paragraph reads as follows:

While it is understandable that ash-Shiryan, who must wear the shoes of his patron and speak with his master's voice, placed the entire blame squarely on the shoulders of the Hariris, the advice he offers remains cogent. To compound matters, it remains to be seen how Lebanon's Sunni public can be convinced that fighting Sunni extremism is not in the interest of Hezbollah and its Iranian patron. After all, that initiative certainly would not offer them any more concessions, particularly since Hezbollah is showing no interest in reviewing its alliance with the Syrian regime. Quite the contrary, it is advancing its supra-Lebanese policies by involving itself in the conflict in Iraq. Especially with that in mind, Ash-Shiryan's piece should be read again by Saad Hariri and his counselors. Still, no one can guarantee that the time for doing so—and for making those important changes—has not already WASS….

Print

Print Share

Share