It Stinks!

Who knew that garbage was so attractive? Well, there's no longer any doubt about it in Beirut. Want proof? Lebanon's garbage crisis began “officially” on July 17 when the Naameh dump, located in the fiefdom presided over by Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, was shut down. That action, which did not come as a surprise since its closure had been ordained several months before, attracted none of the government's attention. It seems that all bets hinged on a last-minute arrangement à la libanaise in which Jumblatt would change his mind and spare the country and its leaders the migraine that would certainly accompany the grand opening of the “garbage file.” After all, that “file” (to use the Lebanese lingo) stinks of the financial and political corruption that has been de rigueur in the country for the last two decades. As things turned out, however, that action became the catalyst for a popular wave of anger fueled by uncreative and inefficient governmental policies. And so, the demonstrations began on Saturday, August 22. As has often been said, the garbage crisis heralded an undeniable end to the March 8-March 14 polarization, which has dominated the Lebanese landscape since shortly after the 2005 assassination of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri and the subsequent withdrawal of Assad's Syrian troops from Lebanon. The fact that the end of that polarization had been announced quite some time ago, however, seems merely tangential. From a practical perspective, the primary actors in each coalition have always sought ways to manage the country jointly (and profit by its management). Yet the objective imbalance between the two has grown by an order of magnitude. As the leader of March 8, Hezbollah has grown remarkably as a regional actor due to its involvement in Syria and other regional arenas. In contrast, the Future Movement (FM) which leads March 14 has continued to lose influence, and at this point, it is questionable whether FM can even be considered representative of mainstream Lebanese Sunni anymore. But despite attempts made by both coalitions before August 22 to maintain some semblance of a “vertical split” (which is how that relationship is referred to in the Lebanese parlance), it is clear that the Lebanese political parties which constitute the two alliances must refresh their "corporate profiles" to ensure their respective constituents remain allegiant. Dutifully, both are hurrying to do exactly that.

Without doubt, some innocuous “solution” (good or bad) will ultimately end the garbage crisis. But when that solution is found, the popular movement will really face its litmus test. Will it continue to address issues that are no less critical than the smelly garbage crisis (such as regular power outages) and possibly far more abstract (such as endemic corruption)? In true Lebanese fashion, though, it will always be too early to assess the legacy of the garbage "uprising." Despite that truism, it is certainly realistic to take some stock from that ongoing movement.

Lebanon’s civil society organizations (CSOs) have enjoyed many years of financial and moral support, most of which has come from the U.S. and the EU. In view of that pedigree, then, Beirut’s garbage protests might well be considered a baptism by fire for those CSOs. While their actions have never before been overtly “political” in nature, the garbage protests mark the first time CSOs have not been used as a sobriquet by a given party or organization. Rather, they are emerging today as bona fide political actors, parties, organizations or simply agendas. That shift should be recognized as a pivotal change in Lebanon's political landscape, the logical consequence of which ought to be a revision of the laws that govern political parties and nongovernmental organizations, especially since current laws date back to 1909—when Lebanon was still part of the Ottoman Empire!

The Other Side of the Looking Glass: LAF vs. ISF

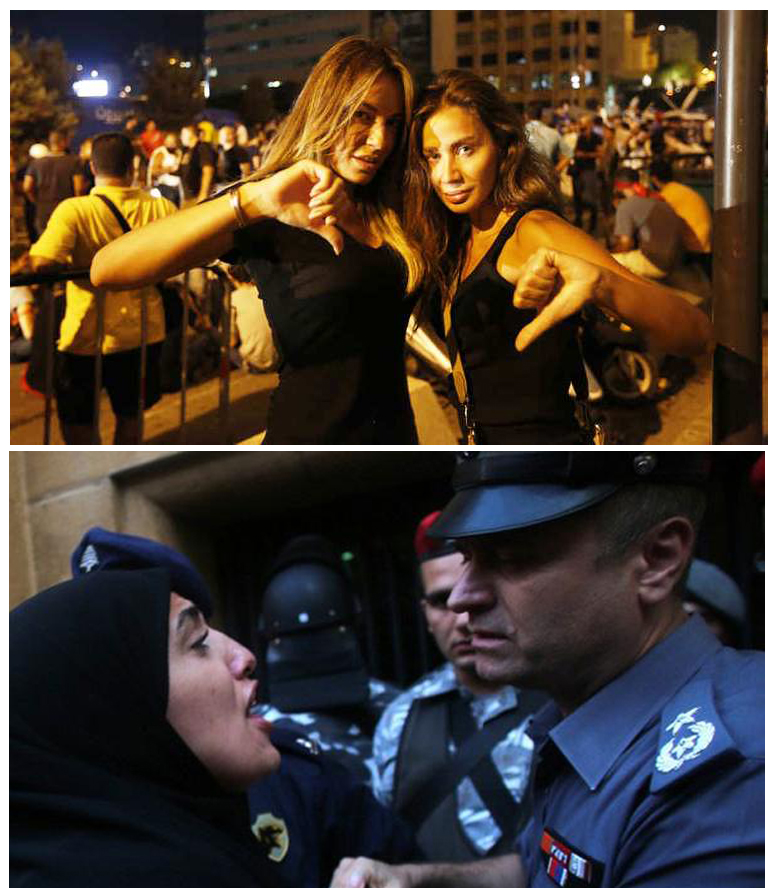

On the evening of August 23, a new concept, "infiltrator," was added to the Lebanese vocabulary being used to describe the garbage protests.[1] In contrast with the good-natured atmosphere that pervaded among the demonstrators that day, a group of “suburban youngsters” systematically instigated clashes with the security forces positioned near the square where the demonstration was taking place. Ultimately, the situation became so unruly that the so-called “civil society” groups that had urged the demonstration demanded that the demonstrators leave the area—and asked the security forces to impose control. Interestingly, the few dozen infiltrators performed so confidently for the television cameras broadcasting the scene live that it appeared they had a very specific agenda in mind. Further, since the identity of those infiltrators is still being investigated, theories about their involvement—ranging from asserting their social conscience to fulfilling some conspiratorial plan—continue to swirl.[2] While the truth about the evening's events will likely end up in the "big book of Lebanese riddles," it is amply evident that “confusion” reigns supreme among Lebanon's security and military bodies regarding who did what, when, how and to whom. In other words, it should be apparent that every time the discussion focuses on Lebanon’s security/military organizations, we must recall that none of them are under the command of a cohesive political authority.

As a result, each organization has its own agenda and each is run by ambitious officials who, based on their respective agendas, are full political partners in some faction of the country's political authority. In order to remain realistic about the events occurring today in Lebanon, and to help forecast what might happen, we must consider seriously the statements and actions of key government representatives, such as Minister of Interior Nohad al-Machnouk. For instance, on the eve of the August 29 demonstration, Machnouk threatened to prevent the Internal Security Forces (ISF) from "escorting" the demonstrators if the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) was not allowed to participate in that mission. Clearly, Machnouk was suggesting that the Sunni-commanded ISF was simply not ready to bear all of the responsibility for suppressing the demonstration (possibly forcibly), while the LAF and its commander-in-chief—who may become a powerful candidate for the presidency of the republic—remained on the sidelines.[3]

Another theory which has continued to gain traction holds that some senior politicians are behind the introduction of the “infiltrators” into the protestors' ranks. General Jamil as-Sayyid, a onetime General Security head who served a lengthy prison term for his alleged role in the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafic al-Hariri, stated unambiguously during a televised interview that the “infiltrators” were being mentored by such politicians. Of course, this "other" theory is equally uncomfortable since it implies that the security agencies associated with those politicians were also complicit in enabling the infiltrators to threaten Lebanon's security by co-opting and "redirecting" the demonstrations.

Investing in "demonstration management" (and mismanagement) is nothing new in Lebanon’s recent history. In fact, the credentials (and other endorsements) of General Michel Suleiman (the LAF commander-in chief from 1998 – 2008) were bolstered because of his apparently astute handling of the huge demonstrations that followed the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafic al-Hariri and the neutrality he is purported to have demonstrated during the events of May 2008, which led to the Doha Agreement. Indeed, those credentials contributed to his election to the presidency. Thus, that precedent, combined with the possible candidacy of the current LAF commander-inchief (General Jean Kahwaji), leads to an inescapable conclusion. Stated simplistically, the best way for the army and its commander (and even the politicians supportive of his candidacy) to be viewed as Lebanon's saviors is by creating and then resolving critical security situations. It is an especially effective strategy, since despite everything, talking about the army and the role it plays in Lebanese politics remains somewhat taboo. Moreover, the LAF's primacy in all things Lebanese is reasserted periodically by the international community, particularly the U.S. After all, which other organization is responsible for preserving Lebanon’s alleged “stability?”

Notably, while the LAF and the ISF are not the only organizations involved in this wrestling match, they are the most visible. Still another, however, is the General Security Directorate. The closest of all such Lebanese security apparatuses to Hezbollah, it is maintaining a very low profile where the garbage demonstrations are concerned. Interestingly, the mandate for the General Security organization includes following up on NGOs and other associations.

The End of a Career…no Insults for Saad Hariri…

The huge posters that surround the grave of the late former prime minister were “profaned” with graffiti. Further, SOLIDERE, the private company the late Hariri founded to rebuild downtown Beirut, was barraged with insults and criticism. After a 10-year political career during which he served as prime minister from November 9, 2009 to June 13, 2011, Saad al-Hariri definitely should have felt indignant about having escaped insult— especially since it appears he has been overlooked completely in the venting of public anger.

A Half-broken Taboo: Are Nasrallah and Hezbollah Part of the “System?”

|

|

The caption reads: |

The Garbage Uprising and Lebanon’s Complex Frontline Grid

Of course, the sectarian dimension associated with the demonstrations can be assessed from a less raucous, more quantitative perspective. On August 30, the day after the largest (to that point) garbage-inspired demonstration, the Amal Movement organized a large-scale rally in the southern town of Nabatieh to commemorate the 37th anniversary of the “disappearance” of Sayyed Moussa as-Sadr. But while the Amal Movement conducts such rallies annually, and although the speech given by Amal head Nabih Berri was moderate and sympathetic to the substance of the popular protest, such spectacles can no longer be considered distinct from the event that occurred less than 24 hours before. At this point, it is challenging to resist the urge to conduct a “comparative demonstration” because of its predetermined conclusion. Nevertheless, while garbage has indeed become the catalyst for thousands of people to seize control of some streets and accuse politicians—including Berri—of being corrupt and wantonly sucking away Lebanon’s resources to suit their own purposes, that denunciation will have little effect on hundreds of thousands of other Lebanese who belong to the clientelist networks of various corrupt, sectarian leaders, and who are ready to heed the calls of those leaders to defer to established sectarian obligations by filling the streets and listening transfixed to their discourses…. [4]

|

|

One of the characteristics of the demonstrations in Beirut that has sparked debate in several |

In language that is less metaphoric and a bit more diplomatic, following a September 3 meeting with Prime Minister Salam, U.S. Ambassador to Lebanon David Hale stated, "The challenges facing Lebanon are serious: there are security, political, economic, and humanitarian problems, so many of them spilling over from the conflict in Syria."8 Mr. Hale also echoed some well-intended yet nebulous advice given by Russia's UN Ambassador Vitaly Churkin (the current president of the UN Security Council), who urged (on behalf of that body) Lebanon's parliament on September 2 "to meet and elect a president as soon as possible in order to put an end to the constitutional instability." Despite Mr. Hale's diagnosis and the entreaty delivered by Mr. Churkin, it does not appear that simply clearing Beirut’s streets of garbage will remove the stench that today characterizes Lebanon. Of course, the (miraculous) election of a president would give the Lebanese a dose of relief, since ostensibly it would contain further deterioration of the cabinet (which would be on par with the overall effect inspired by the formation of the Salam government). As all Lebanese have witnessed, however, the election of a new president is no easy task—nor is its eventual outcome guaranteed to be positive.

In view of the foregoing and until further notice, no one should expect good news to emanate anytime soon from the small country sandwiched between the rotting remains of Syria, the eagle eyes of Israel and a sea increasingly crowded by boats chock-full with refugees seeking to escape Lebanon s stinking shores in favor of some fanciful El Dorado...[5]

[1] Coincidentally, the same concept surfaced almost simultaneously in Iraq. On August 26, the Lebanese daily as-Safir reported that during a meeting with his ministers of interior and defense, Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar al-Abady warned that “infiltrators” were trying “to poison the relationship between demonstrators and security forces.”

[2] The minister of interior recognized personally that the violent response to the situation by the security forces was “excessive,” and a subsequent investigation of those events resulted in disciplinary measures being taken against some of the organization's officers and patrolmen.

[3] An-Nahar, August 29, 2015.

[4] This applies as well to General Aoun's Free Patriotic Movement, the members of which began large-scale demonstrations in Beirut on September 4.

[5] About the same time the garbage protests began in Beirut, a boat that presumably left the Lebanese port of Tripoli filled with refugees sank off the Turkish coast. Those aboard included Palestinians who fled the Yarmouk refugee camp near Damascus and had sought refuge in Lebanon's Beddawi camp (North Lebanon). Open sources coupled with information obtained by ShiaWatch confirm that Lebanon's market in “boat people” is flourishing. Interestingly, the LAF announced September 6 that it arrested two Palestinians in the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp (again in the North) for their involvement in smuggling refugees into Turkey. The LAF also raided an apartment near the Beddawi refugee camp in which 21 Palestinians were preparing to depart Lebanon illegally. For more information, see “The death of nine refugees 'who sailed from Tripoli'… A bad omen?.

Print

Print Share

Share

.jpg)

.jpg)